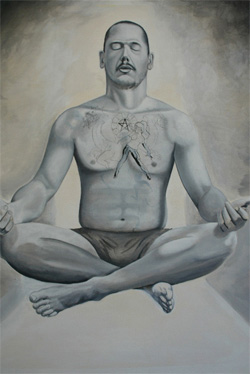

Scott McKinstry (above), Self Portrait (below), acrylic on canvas, 42” x 51”, unfinished

In Emrick’s view, it is in everyone’s best interest that prison arts programs exist to provide a buffer.

“Part of my pitch for the art program is that we’re helping guys come out better human beings. If you have someone who is locked up and they’re left in this culture that’s very negative, they’re going to come out angrier — or at least the same.

“If you have a chance to bring in some humanity, to bring in some outside professional artists who interact with them, who give them criticism done in a professional way and also give them skills, then that really helps transform them. We’re providing safety for the community because we’re having someone come out who’s not going to be angry, who’s not going to be bitter.”

The inmates in the Arts in Corrections program speak of the program’s snug art room as a sanctuary from the greater climate of acrimony in the prison. Scott McKinstry, an inmate who paints gallery-quality acrylics despite only being in the program for three years, points out that Arts in Corrections classes have an environment entirely different than the rest of San Quentin.

“The biggest thing in prison is segregation. Whites are here. Blacks are here. Mexicans are here. Asians are here. Everybody segregates and there are lines you don’t cross. You don’t play with each other. You don’t horse around. You don’t call each other names. You have that barrier. You come in here and we don’t have that. It’s like escaping that.”

In the art community, you meet a lot of people who talk about “living for art.” For the men in the Arts in Corrections program, that statement is more than just a platitude. These are people who might not be alive if it wasn’t for art.

Life in San Quentin offers numerous chances to be sucked into the cycle of violence and revenge. Being a part of the program gave McKinstry, who had never made art until he was several years into his fifty-one-years-to-life sentence, a chance to free himself from that malicious eddy.

“I bit into the prison politics. I was violent. I dealt with issues of disrespect or disagreements through violence like most all of us do. I don’t do that anymore.”

Not only has the program given McKinstry a way out of violence, it has also helped him build coping skills.

Not only has the program given McKinstry a way out of violence, it has also helped him build coping skills.

“From what I’m doing now, in expressing myself, my anger level has fallen way down. I’ve learned to deal with issues, not just swallow them and let them build up and have them come all at one time. I can get them out on canvas.

“Even if it’s frustrating and it doesn’t come out right, I still got it out in a positive way. It still may be aggressive, but it’s between me and an inanimate object, not between me and someone else.”

Even though McKinstry, who has served on various prisoner leadership and activities councils over the years, may never leave San Quentin, he is using the positive attributes he has developed in Arts in Corrections to help others who will.

Twenty-year program veteran Ronnie Goodman is one of the men McKinstry is currently collaborating with on a mural adjacent to the San Quentin art room. As Goodman points out, being a part of Arts in Corrections has not only changed his life inside prison, but given him a vision for a positive life outside it as well.

“I think art teaches you patience and compassion and really to enjoy the smallest things in life. I wake up and see the colors of the sky and see the birds flying. I never really focused in on that. Then you think about being free. It would be nice to be able to go to the park, kick back and relax and sit down and draw. To block off everything else in life and find your own little space.”

While the prison artists await their chance to rejoin the outside world, their voices are periodically carried out via shows of their work. As Emrick puts it, “They look at it as a way to get their work out and to get exposure, but also for them to show that they are something other than just this animal locked up inside, that they have this whole human side to them, and that they have a way of expressing their beauty.”

The proceeds raised from the selling of the inmates’ art goes not only toward funding Arts in Corrections but also to support youth diversion programs.

It is very easy to psychologically compartmentalize those inside the criminal justice system as having failed society. They chose to break the rules, the reasoning goes, and in doing so chose life as outcasts.

But these choices, as hideous as they may have been, were not made in a vacuum. It is just as valid to claim that society fails certain people, just like it was doing to that teenage girl at the symposium. Not everyone grows up having their needs met. The prison system, through programs like Arts in Corrections, gives the formerly ignored a chance to be heard.

– Buck Austin