The incessant recycling of popular culture is one of the more loathsome qualities of American entertainment. Television shows based on movies, movies based on television shows, video games based on both, and every permutation in between crowd our media landscape.

The incessant recycling of popular culture is one of the more loathsome qualities of American entertainment. Television shows based on movies, movies based on television shows, video games based on both, and every permutation in between crowd our media landscape.

At best, remakes like The Brady Bunch Movie remind us how much we liked the original. At worst, ill-conceived rehashes like 2005’s Bewitched make us feel an awful cultural claustrophobia.

But thankfully, this is not the case with Sci-Fi Channel’s re-imagining of the 1978 series “Battlestar Galactica,” whose third season concluded in March. Executive producer Ronald Moore has created a fascinatingly complex story that is not only an entertaining sci-fi series, but also sheds light on the evolution of television drama over the past thirty years.

Like a good cover song, “Battlestar Galactica” is more than an updated version of its source material; it is a reinterpretation that meditates on the original and produces something totally new.

“Battlestar”’s re-creator is no stranger to updating classic science fiction. A long time “Star Trek” fan, Moore began his television career writing for “The Next Generation.” Yet unlike “The Next Generation,” which was a modernization of Gene Roddenberry’s 1966 vision of adventure tales in a utopian future, the new “Battlestar” turns the original premise on its head to great effect, bringing it screaming into the 21st century.

“Battlestar Galactica” is not only an entertaining sci-fi series, but also sheds light on the evolution of television drama over the past thirty years.

Conceived and promoted as a reaction to the immense popularity of Star Wars, the original “Battlestar Galactica” chronicled the adventures of a distant human civilization at war with an army of robots. These “cylons” were named after their creators — an extinct race of reptilian aliens. The humans, whose civilization was destroyed in the initial cylon attack, race across the galaxy in search of a new home on a fabled planet called Earth.

Though some of the production values appear laughable now, the special effects were groundbreaking at the time, running the series budget up to an unprecedented cost of a million dollars per episode.

The most significant difference between the two versions, the one simple change that transforms the meaning of the entire story, is the first thing revealed in the new series’ opening sequence. As the music starts, a title appears reading: “The Cylons Were Created By Man.” Whereas the 1978 version portrays a one-dimensional struggle between good and evil — the remaining humans against their merciless alien attackers — the new series centers around a darker, more layered premise steeped in moral ambiguity. Humanity created its own worst enemy.

Whereas all of the cylons in the 1978 series were “toasters,” shiny metal robots with nefarious forms reminiscent of Darth Vader, the new series features several models of cylons who appear human. Some of these beings even believe they are human, living among humans until a switch flips in their programming and their secret identities make them useful for sabotage and subterfuge.

The derogatory slang for humanoid cylons on the show is “skin jobs,” a very direct reference to the film Blade Runner about a detective tracking down rogue humanoid androids in a similarly dark and frightening future.

The additional layers of complexity evident in the new version of “Battlestar” extend to its human characters. The heroes of the 1978 version were good guys crusading to save humanity from evil robot assailants, but the characters on the current series are multi-dimensional. The hardnosed admiral, his alcoholic colonel, the self destructive hotshot pilot, and a host of other characters with very real, very human flaws allow the show to delve into moral and ethical dilemmas about the nature of good and evil.

Nowhere is the difference in narrative complexity between these shows more obvious than in the character of Baltar. A comically villainous Count who collaborated with the cylons to orchestrate humanity’s demise in the original series, the new Baltar is a brilliant scientist seduced into becoming an unwitting cylon accomplice who then tries to cover up his involvement out of self-preservation.

In the 1978 series, Count Baltar is assisted in his evil machinations by a cylon named Lucifer. But on the current series, he is counseled by a beautiful cylon woman whom he loves. Since she appears only to him, we’re never quite sure whether her advice is real or just some facet of our anti-hero’s inner monologue.

Dr. Gaius Baltar on the new “Battlestar” series is selfish, vain, and cowardly. But he’s portrayed with a deftness that forces you to relate to him, to understand that his flaws and deceptions are motivated by fear and ego. If the struggling crew of Galactica represents the best aspects of humanity, he represents some of the worst, but is human nonetheless.

Looking at these two series reveals much about the evolution of television drama over the past thirty years. Modern special effects and larger TV budgets allow producers to realize show aesthetics in a way they could not in the 1970s. But most importantly, current TV trends that encourage complex narrative structures and layered, conflicted characters allow the writers of the series to realize the story in a way that most television didn’t thirty years ago.

It seems appropriate, then, that season three concluded with some of the characters reciting a version of “All Along The Watchtower.” Though everyone gives the song’s original author plenty of credit, Dylan himself admits that Jimi Hendrix is the one who got it right.

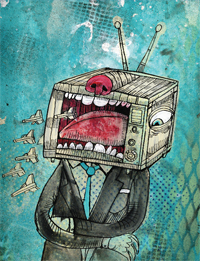

– Column by Tom Hoban, illustration by Ferris Plock

Tom Hoban works in cable television in New York City. Ask him why he thinks Aristotle would have loved “Saved by the Bell.”