From his self-described “funky workshop” in Tucson, Arizona, machinist, dive master, musician, and artist Wayne Martin Belger creates custom pinhole cameras, one for each of his evocative photo series. The result is a study in relationships – between tool and product, artist and subject, intimacy and distance.

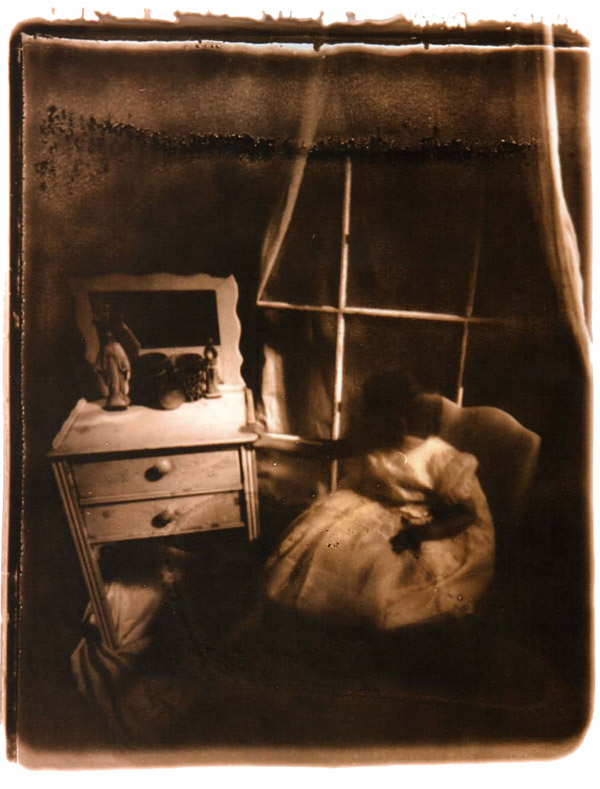

“I think this type of photography is far more real than others,” Belger explains. “With pinhole, the same air that touches my models can pass through the pinhole and touch the photo emulsion on the film. There’s no barrier between the two. There are no lenses changing and manipulating light. There are no chips converting light to binary code. With pinhole what you get is an unmanipulated, true representation of a segment of light and time. With some exposure times getting close to two hours, it’s kind of like an unsegmented movie from a movie camera with only one frame.”

This direct relationship of light and air, coupled with the photos’ otherworldly qualities, create the simultaneous distance and intimacy you feel gazing at old family photographs – unknowable people in antiquated clothing with whom you share the bonds of blood.

“Because the camera is in direct relationship with the subject, there are no barriers between the photographer and the subject. I don’t see how I would be able to connect with my subject and produce what I want using something made in Germany or Japan. I don’t even own a camera that wasn’t made by me.”

An image taken by Belger of the Taj Mahal using his Dragonfly camera appears in the tintype shades of an old postcard.

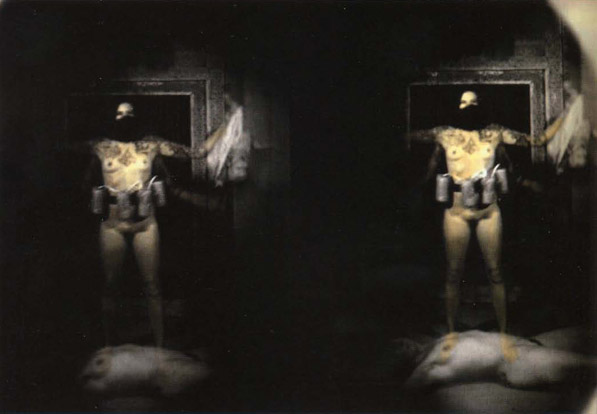

“Dragonfly was created as an altar to a nine-year-old girl that passed away. I worked as an investigator in child recovery years ago. One case I worked on for sometime was a nine-year-old girl named Cortney Clayton who had been missing for over a year. Over that year I became close to family. Cortney was found dead not far from their home in Texas. Cortney’s death had a major impact on me. The camera’s subject is children. Children are the subjects of the photos. In the photo you can see two ghosts of a little boy and girl. I thought that was nice for the Taj.”

“Because the camera is in direct relationship with the subject, there are no barriers between the photographer and the subject.”

Two ghostly figures of a little boy and a little girl pose stiffly in front of the monument. The stillness, the apparent remoteness in time, the formal symmetries of the monument, and the exotic destination combine to create an image that seems in many ways rigid and posed, yet there is an obvious warmth and sincerity in Belger’s gaze.

“Some of the ‘ghosts’ in my photos are people that stood in front of the camera while it was exposing the film. Because the cameras don’t really look like cameras, most people had no idea I was taking their photo. So they would move, creating a ghost. Some of the other ghosts in my shots I can’t explain.”

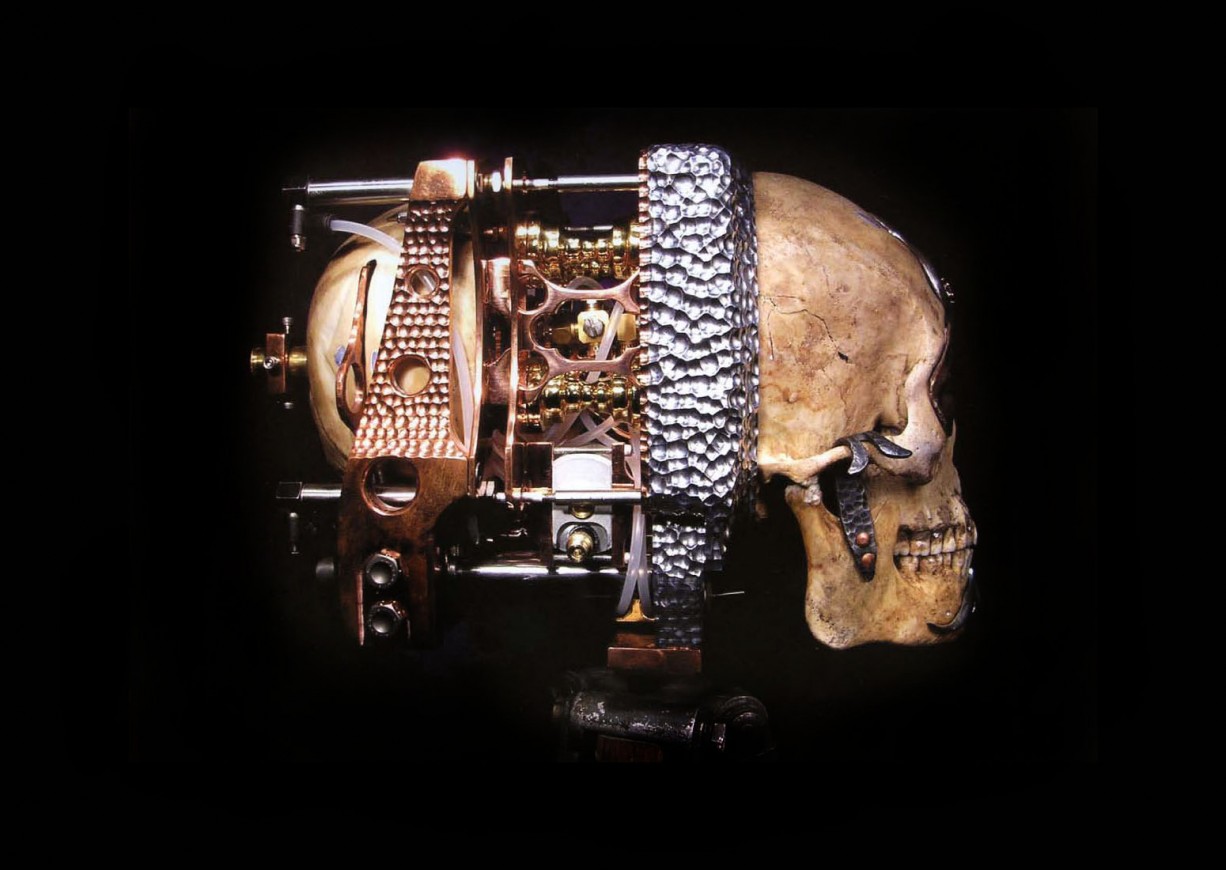

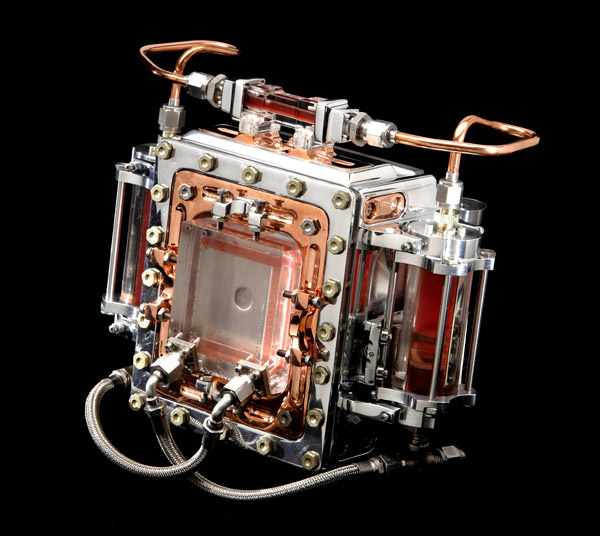

Perhaps none of Belger’s cameras have created as much stir as those that employ human body parts, such as the Heart camera that contains an infant’s heart, recovered from an anatomy lab, which he uses to photograph pregnant women. Belger created another camera with the skull of a 13-year-old girl, scavenged from an antique anatomy kit. A pinhole is drilled into her forehead and her face decked with jewels. Recently, Belger completed Untouchable.

“[The camera] was inspired by one of my best friends that has the HIV virus and my quest for understanding it. I named the camera Untouchable because of the similarities of the untouchables in India and how some with the virus in the US are treated. My friend is the one who donated the blood and is in the first series of photos from the camera. A photo of him is also in the camera itself.”

“With over 130 parts the camera has been the most intense construction-wise yet. The blood is held in a sealed circulatory system. There are two clear vials of blood on each side of the camera. The one on the right contains a magnetic hand pump that pumps HIV-positive blood between two pieces of acrylic that are 0.0005 inches apart and positioned in front of the pinhole. This creates the equivalent light restriction to a #25 red filter that you use in black-and-white photography for contrast. So far I’ve done five photo shoots of people with HIV in San Francisco. I now want to expand the series to Africa and India to be a geographic comparison of people with HIV.”

The resulting “Bloodworks” photos have the ghostly qualities of his other images, but without any specific, recognizable background. Instead, solitary figures crouch in the center of a hazy field of solid black or red, their bodies reduced to simple outlines without individual features. The figures become iconic symbols of the disease, while their peculiar body postures assert their individuality. As with so many of Belger’s most moving works, the photos are both intimately personal and achingly removed.

“The response has been amazing,” Belger says. “With people where HIV has touched their life, it’s been emotional, personal and I’ve been told it’s about time.”

Discussing the HIV series, he explains, “With most of my work I try to make the spectrum on the subject as wide as possible – ultimate beauty with ultimate villainy. So responses have been extremely wide.”

The artist is never one to shy away from controversy, but even his most politically sensitive projects are handled with such grace and sincerity that it is difficult to find offense. In one of his most recent projects, Belger applies this respectful approach to the issue of Tibetan independence.

“One of my latest and most interesting cameras is called Yama. It’s a stereo camera made from a 500-year-old Tibetan skull. Yama is the Tibetan god of death. The skull was blessed by a Tibetan Lama for its current journey, and I’m working with a Tibetan legal organization that is sending me to the refugee cities in India. The photo series will be of a 500-year-old homecoming through the eyes of a Tibetan Lama.”

“Yama’s eyes are cast from bronze and silver with a brass pinhole in each. A divider runs down the middle of the skull creating two separate cameras. A finished contact print mounted on copper is inserted into the back of the camera to view what Yama sees in 3D. Yama is made from aluminum, titanium, copper, brass, bronze, steel, silver with four sapphires, three rubies (the one at Yama’s third eye was $5,000) and seven opals inlayed in the skull. The film loading system is pneumatic – a 300psi air tank in the middle of the camera powers four pneumatic pistons to move the film holder forward and lock it into place. The switch to open and close the film chamber is located under the jaw.”

Belger’s work is intensely spiritual – a series of reliquaries, altars, and meditations. The Los-Angeles-born artist says, “For the first part of my life, I lived in a primarily Hispanic area. Family and the church were the cornerstones of the community. When I was young, the Catholic Church seemed very magical to me. I didn’t see any difference between a priest at his altar and a wizard in his castle. Both said things I couldn’t understand and gave great importance to their sacred objects and potions. As the priest has his tools of gold and silver and blood and body to be in direct relationship to the subject Jesus, I create my tools of aluminum and titanium and blood and body to be in direct relationship with the subjects they are created for.”