Tonight in Santa Fe, it is frigid and damp. A storm passed through earlier and snowclouds are forming to the west. Outside the Lensic Theatre, located in the maze of downtown streets among khaki-colored adobe buildings, stand well-dressed and anxious concertgoers in line for tickets. The half-full lobby smells like leather and perfume. The band inside is a group of turbaned, robed Saharans called Tinariwen.

Five light-skinned African men shuffle gently on a stage devoid of decoration — with only amps and microphones — their physical appearance alone making a dramatic statement. Each holds an electric or acoustic guitar, electric bass, or a hand drum. Though Tinariwen’s music is hypnotic, transcendental, and groove-oriented, they appear stoic and self-controlled.

Audience members stand in sharp contrast to the band; they’re dancing like it’s last call.

Halfway through the set, Bob Martin, the Lensic’s general manager, orders the house lights on. The aisle dancers are violating the city’s fire code, he says, and the show would end early if everyone did not return to their seats.

“It doesn’t matter what the band wants,” Martin curses. “This is my space.” Some boo. Others sit down. The band appears passive and indifferent, though none of them speak English and likely don’t know why this large, red-faced man is shouting at the audience.

Concert resumed, Tinariwen plays with a renewed fervor, inciting the audience to stand up and shake its collective ass. Songs begin similarly: with an electric guitar melody, muted and distortionless. The band joins in, playing syncopated countermelodies and basslines that are commanding but unobtrusive. A guitarist calls out a line; the others respond in unison.

The songs build on a single groove or riff, recalling old blues artists who found innumerable ways to reinvent twelve-bar chord progressions and Bo Diddley beats. When Elvis borrowed liberally from bluesmen in the 1950s, he sparked a musical tradition that links the Beatles and Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. But Elvis was from the wealthiest country on Earth. Tinariwen is from an impoverished place that many of us couldn’t find on a map.

The name Tinariwen translates as “empty places.” Indeed, the band’s sound, image, history and ethnicity are all tied to one of the remotest regions of the world, northern Mali. This unforgiving chunk of the central Sahara was a French colony until the 1960s, when Mali and neighboring Niger gained independence.

Tuaregs, nomadic camel herders who have roamed the Sahara for centuries, were unwittingly caught in this power move. They’ve been suffering the consequences of it ever since. The newly formed Malian and Nigerien governments wanted the nomads to settle down and integrate into society. Some did. Others refused. Battles and destitution ensued.

Guitarist/vocalist Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, whose father was killed by Malian fighters, fought for Tuareg independence in the 1970s and ‘80s. He co-founded Tinariwen in 1982 at a Tuareg military training camp, practicing guitar between military exercises. He listened to northern African pop stars, but also to such disparate groups as Euro-dance group Boney M and American country singer Kenny Rogers. Rebel leaders used Tinariwen’s first albums, recorded on cassette tapes and passed around by fans, as anti-governmental war propaganda.

As Tinariwen’s reputation grew, the Tuaregs made progress. Rebels in Mali signed a peace accord and ceremonially set their weapons afire in Timbuktu in ‘96. Five years later, Tinariwen recorded their first CD, The Radio Tisdas Sessions (never mind that the band was by now nearly 20 years old), and toured Europe. Westerners took notice.

Last year, Tinariwen opened for the Rolling Stones; last April, Robert Plant invited them onstage to play “Whole Lotta Love.” Tinariwen played the Montreux Jazz Festival alongside Carlos Santana. Bonnie Raitt adores them. I first learned about Tinariwen while reading an article whose lofty subheadline asked, “Is Tinariwen the greatest band on Earth?”

National Geographic is filming Tinariwen’s performance in Santa Fe tonight. The show ends with nearly everyone on the bottom floor of this performance hall off their chairs and dancing, to Hell with the fire marshal and venue management.

The group blasts into a chugging anthem that sounds remarkably like an Africanized version of “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.” The audience resembles a fevered Pentecostal congregation, whose members lose themselves and surrender helplessly to the rhythm. Tinariwen rocks beneath their robes and turbans.

Moving through the crowd after the show, I overhear a woman in the front row say to a sweaty aisle dancer, young enough to be her son, “You know, you assholes really ruined that concert.”

“That’s rock ‘n’ roll, baby,” the kid snaps, barely missing a beat.

Audience members push toward the merchandise table in the lobby, making passage almost impossible. The band’s tour manager, Bastien Gsell, is selling T-shirts and CDs as fast as his hands will move. If Tinariwen’s three albums (The Radio Tisdas Sessions, Amassakoul, and Aman Iman) had each cost $50 tonight, they’d still sell out. The fans here border on fanatical.

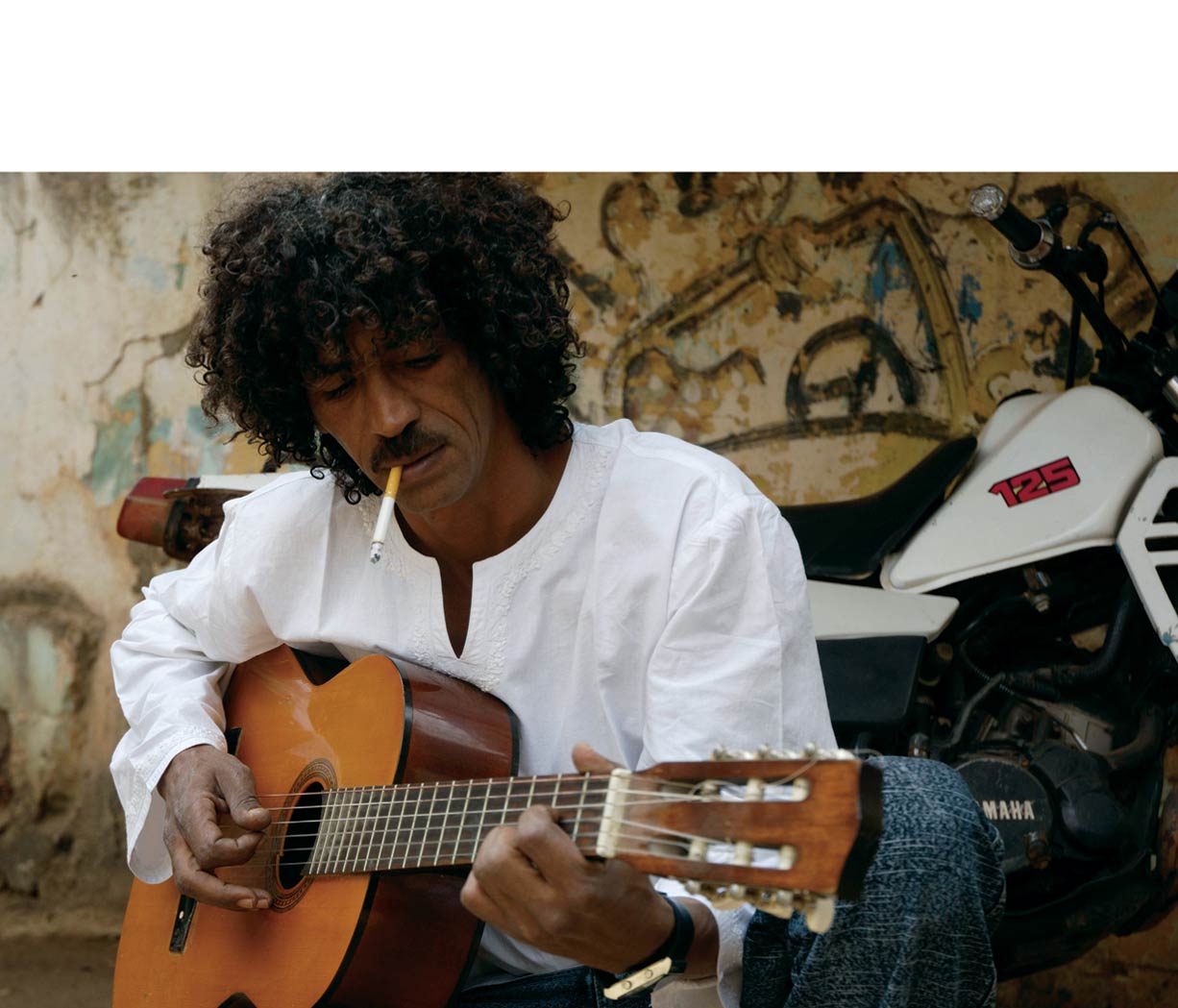

Past the maze of backstage hallways, downstairs, in an overlit dressing room fit for a troupe of ballerinas, quietly sits acoustic guitarist / singer Abdallah Alhousseyni. Round-faced and moustached, he is exhausted but accommodating.

Next to him sits Valerie-Milenka Repnau, a sturdy, blonde Los Angeles resident who drove fourteen hours to be here tonight. Behind them, other band members change from their robes into slacks and buttondown shirts — Western clothes. They carry backpacks. This does not seem incongruous to Alhousseyni, though it’s odd to see his bandmates morph into something different. Offstage, they look like Americans.

Is Tinariwen’s whole desert-warrior aesthetic just an act?

Alhousseyni thinks and pauses. “From the beginning, we weren’t a traditional group,” he finally says in French, with Repnau translating. That much is certain.

Their press materials boast that Tinariwen is the first Tuareg band to ever employ electric guitars. Tinariwen is a small army of six-string players; traditional Tuareg music doesn’t even involve guitars. There’s no name for the genre the band fits in. They call it, simply, “guitar music.” It’s become more popular recently, with other groups like Toumast riding a surge of attention devoted to west African blues that was arguably sparked by Ali Farka Toure in the mid-’90s.

“They’re celebrities,” says Dr. Susan Rasmussen, an anthropologist who’s studied the Tuareg for 25 years and has met Tinariwen in their hometown of Kidal, Mali. “They’ve served an interesting role, as unofficial ambassadors between the government and the rebels,” she adds. “[But] they also serve as an inspiration to the local youth. Because of all the problems in Mali, a lot of the youth are unemployed. Tinariwen serves as a role model.”

The band’s themes reflect the shift in emphasis. Early on, frontman Alhabib’s songs directly spoke of war and famine, pointing fingers at the government. The songs on Aman Iman (World Village) are more positive, speaking to general themes of peace and education.

Lyrics aside, the guitars behind them have grown more aggressive and hard-edged. On a dressing room counter next to Alhousseyni, Repnau rummages through her purse looking for a business card. She pulls out a CD: Nirvana, Nevermind. She let the band hear it for the first time yesterday.

No doubt, the shifts in Tinariwen’s music reflect their ever-expanding tour schedule and exposure to different styles. Since their first international tour eight years ago, Tinariwen has perhaps traveled more than most Americans. Yet their songs still tell the stories of their home — bleak tales of survival and cautious hope, desperation and escapism.

On “Tenere Dafeo Nikchan” (“I’m in a Desert with a Wood Fire”), frontman Ag Alhabib intones, “My heart oppressed and tight / And I feel the thirst of my soul / Then I hear some music / Sounds, the wind / Some music which takes me far, far away”. On “Arawan,” another song from their 2004 release Amassakoul, Alhousseyni sings, “Nobody cares about / The people of the desert who are suffering from thirst.”

And the struggle continues. The day after Tinariwen’s Santa Fe gig, two journalists, Moussa Kaka and Ibrahim Manzo Diallo, were jailed for reporting about the Tuareg resistance in Niger. The Nigerien government had been tapping Kaka’s phone conversations for months, and is now seeking life imprisonment.

This will likely increase hostilities between the two sides, which renewed military campaigns against each other in mid-2007. Niger claims the rebels are trafficking drugs and arms. The rebels say the government is trying to squeeze them out of profits made from uranium, which is found throughout the Tuaregs’ homeland.

The Bush Administration has supported the Malian and Nigerian governments, claiming they’re vital in assisting with the war on terror. Mali’s army spokesman has branded the Tuareg rebels as terrorists. US Special Forces have been in the region. This leaves Tinariwen in the awkward position of traveling through a country that has sided with their enemy.

So I ask Alhousseyni: what’s Tinariwen doing to support the rebellion?

He looks directly at my notebook while answering, and responds after a few seconds of uncomfortable silence. “We play a lot of free shows back home.”

That’s rock ‘n’ roll, baby.