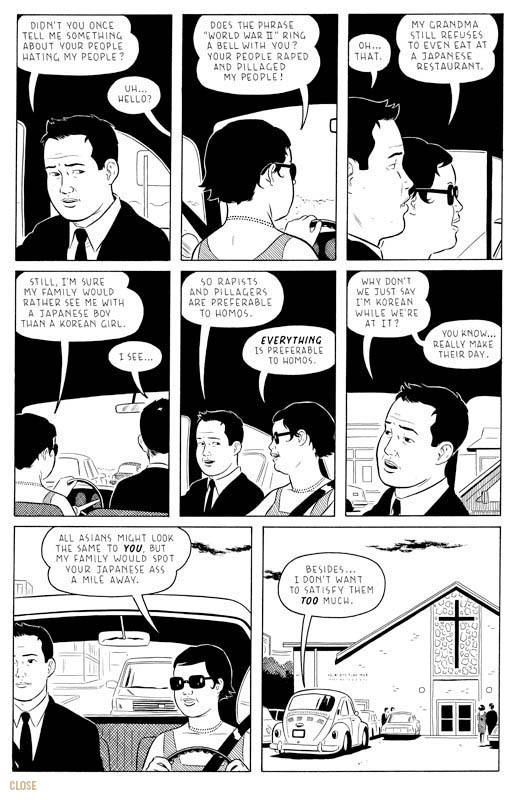

When I first read Adrian Tomine’s graphic novel Shortcomings more than a year ago, I was struck by two things: the comic’s sensitive and honest portrayal of modern race relations, and the wonderfully clean art style. The former proceeds mostly from Tomine himself, a fourth generation Japanese American. The latter is strongly inspired by modern masters of the medium like Daniel Clowes and the Hernandez brothers, and it results in evocative illustration that recalls classic comic art of the 1950s and even Roy Lichtenstein.

Shortcomings is actually made up of the final three issues of a longer comic series by Tomine called Optic Nerve. The earlier issues, an anthology-style treatment of modern urban life, introduce some of the same themes as Shortcomings, but with a bigger emphasis on general human experience than on the tensions of ethnic identity.

The first issue of Optic Nerve (published April 1995 by Drawn and Quarterly) includes five stories, the first of which is “Sleepwalk.” At first glance, the story is about a hermit-like twenty-something named Mark, whose ex suddenly calls and invites him to dinner on his birthday. Although they have a great time, he misconstrues the situation and tries to kiss her. Her rebuff is almost like being dumped all over again, and the distraught Mark gets into a car accident. He isn’t hurt, however, and the other driver is shockingly nice — and a car thief — who soon splits, leaving Mark alone with the damaged cars.

“Echo Ave,” the second story, is an oddity. A bored married couple discovers that the tenants across the street don’t have curtains on their windows, and later watches a naked couple (one’s wearing rubber gloves) have sex. The husband explains away their voyeurism: “They look like the kind of weirdos who’d get off on that anyways.” When the wife leaves the room, something undefined happens across the street and her husband tells her not to look at the window. He holds her, silently, in their own darkened room. Again, the story features characters who try to connect to other people by half-measures, only to encounter disaster and (implied) murder.

The sexual dysfunction continues in “Long Distance,” where a woman is coerced into phone sex with her strange boyfriend in order to salvage their long-distance relationship. And the ambiguity of Tomine’s illustration is revisited in “Drop,” where the narrator’s dad visits relatives in Japan for the first time and mistakenly steps backward off a cliff on the highway. The reader isn’t sure if there’s anything but the “void” to stop his fall, and the final image is simply a flailing hand in a black frame.

The last story, “Lunch Break,” is something else entirely. The almost wordless opening shows an elderly woman making a lunch and then eating it in her parked car. She recalls when she used to bring lunch to her boyfriend, when she was a young woman, and how they made plans for the future. The story then cuts back to the elderly woman, who returns to her house and throws away the sandwich, half-eaten, in despair.

The combined impact of the five stories leaves the reader with one main thematic impression, the subject that no one likes to mention — the malaise and shiftlessness of the modern adult. Mark has no capacity for forming meaningful relationships; the bored marrieds must seek excitement from voyeurism; love in “Long Distance” means discomfort, coercion, and stilted phone-sex scripts; and the dad in “Drop” is punished for seeking out his roots. The elderly woman, moreover, shows that the connections we do form are fleeting and are wiped away easily by time.

In writing stories that would later be classified as “indie” or “emo,” Adrian Tomine shows us how lonely those states can really be.