Melbourne, Australia-based visual artist Adam Cruickshank has been hard at work destroying paintings. He discovers them scattered around secondhand shops, brings them home, and proceeds to paint on top of them, cut them up, or rearrange them, ultimately crafting an entirely different image than the primary creators ever intended for their work. He’s done this to purposefully piss viewers off, exhibiting some of these remixed paintings in a show he curated in November of 2009 (cheekily titled OMFG!) that focused on the context of offensiveness.

When speaking about these pieces, though, he doesn’t even bother to describe what they look like — what matters is the idea itself. And with this gesture, Cruickshank turns Marshal McLuhan’s phrase “the medium is the message” on its head. “I’m not driven in the first instance by the way things look but rather what they’re about,” he explains. For this artist’s artist, the message is the medium.

Though he was born in Australia in 1970, Cruickshank spent most of his teenage years living in places as disparate as Malaysia and Port Moresby, New Guinea, while his father was in the Air Force. He says that living in these sorts of places required a closeted type of lifestyle, where freedom of expression was not necessarily encouraged, and the family really had to rely on itself. (Funnily enough, The Economist rated Port Moresby one of the least livable cities in the world in 2005; in the same study, Melbourne was rated as one of the most livable cities.)

When Cruickshank’s dad left the services, though, the family was so accustomed to a nomadic lifestyle that they continued to travel the globe.

From a very early age, Cruickshank knew he would grow up to pursue a career in art. “I never really had those phases of wanting to be an astronaut or wanting to be anything other than an artist because I was told that’s what I was, and it’s what I’ve always thought I was,” he divulges. Cruickshank later attended Queensland College of Art in Brisbane, where he began to experiment with vastly different materials and hone his ideas on viewership in public space.

He has since spent time as a sculptor, graphic designer, video artist, assemblagist, illustrator, and designer — laying out pages for a number of magazines, creating shirts for brands including 55DSL and Boxfresh, and designing characters for a Nike street campaign (“No, I don’t love to draw little monsters for Nike, to be honest, but it’s certainly better than my current day job,” he admits. “I’ll take it; it’s a lesser evil.”).

“Wouldn’t it be nice if you could sum all this stuff up? More weird and commercial and for the kids? Big business co-opts so much underground culture, why don’t they just do the big thinkers of our time?”

In the early 2000s, Cruickshank began dabbling in the world of street art, erecting wheatpastes on the walls of Amsterdam, London, Sydney, and other major metropolitan areas. Such a transitory childhood existence gave him a varied and nuanced perspective on public-versus-private space; he had inhabited vastly different cities and towns of all sizes and levels of wealth and development.

He wanted to explore these issues by putting up work outdoors but did not want to get casually lumped in with the street-art movement. He clarifies that any work he’s put up is done so because of the idea germinating behind it. “Whether it’s in a gallery or it’s in public space, or if it’s a drawing or if it’s a sculpture, the idea always drives it into that place rather than, ‘Oh, I wanna do work on the street,’” he says.

Due to this, in conjunction with the recent stigma of trendiness attached to street art, he’s shied away from it as of late. However, he was inspired in 2008 to put up a series of screen prints reading “Populism” in heavily illustrated lettering on the streets of Berlin, where he was stoked to see the city’s tolerance of — and even appreciation for — the form. “You would see people very deliberately checking it out,” he says. “It was almost a nice thing to find on your building rather than a bad thing.”

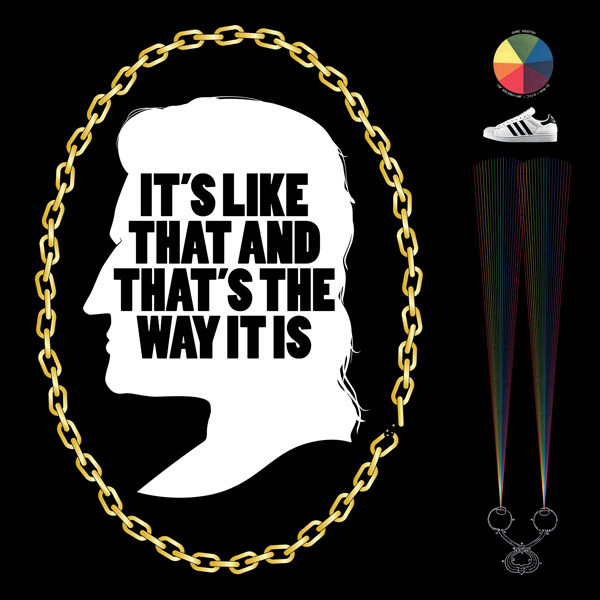

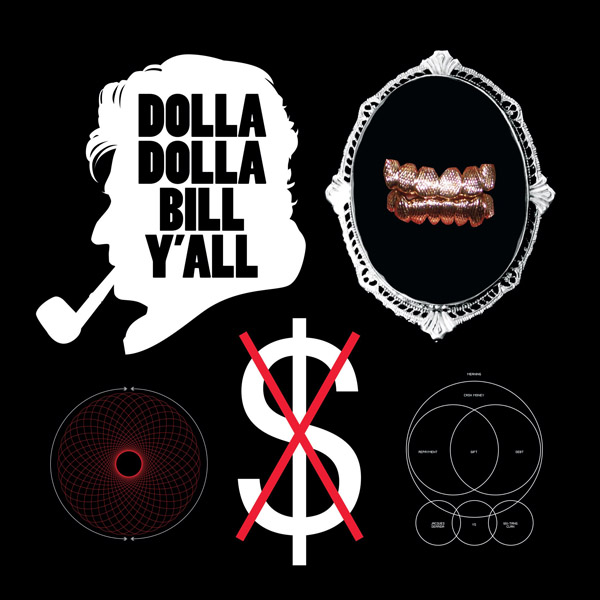

In early 2009, Cruickshank was able to leverage his concerns about showing work outdoors with the limitations that indoor galleries offer by putting up a poster series, “Philosopher Kings,” at a window-display-cum-gallery space on the façade of the Majorca Building in downtown Melbourne. These images cheekily pair popular hip-hop lyrics from the likes of Run DMC and Wu-Tang Clan with well-known but often little-understood concepts advanced by Western philosophers including Isaac Newton and Jacques Derrida.

Though Cruickshank listens to a lot of hip hop, the idea was generated while reading a philosophy book. “I was thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if you could sum all this stuff up? More weird and commercial and for the kids? Big business co-opts so much underground culture, why don’t they just do the big thinkers of our time?’” he says. While putting back a few pints at the pub with friends, they began pairing wordsmiths, driving at simple comparisons that would resonate with anyone: “We were like, ‘How about Simone de Beauvoir and…Peaches!’ It’s a pretty fun game,” he says, chuckling.

For another recent project, Cruickshank took on his complex feelings towards the world of marketing with a combination of sculpture and assemblage he’s dubbed the “Enhanced Awareness Campaign.” These brightly colored, gaudy plastic concoctions are meant to ridicule — or perhaps praise — successful folks in consumer branding and advertising.

When asked if they represent a definitive statement against consumerism, he replies, “There are certain elements of irony and sarcasm in those trophies — that’s undeniable. You could easily read it as criticism, but conversely you could read it as some kind of weird, psychedelic joy of the same stuff.”

To assemble the trophies, he salvaged plastic bits and baubles from outside a closed bowling alley. Riding past the forgotten structure on his bike one day, he spotted the remains peeking out of a dumpster, and they reminded him of his youth in Malaysia. “My parents and I were real kingpin bowlers,” he says.

“I had all these tiny little bowling trophies as a kid, but I hadn’t played for ages. So then seeing [these] huge, half a ton of trophies in this bin outside the ex-bowling center, I just couldn’t contain myself. I had to have them all.” He immediately realized that they could function as a material for art making.

But then, in Cruickshank’s world, so can anything.