The work of Gregory Jacobsen depicts a slaughter. His work reveals the primal and wondrous parts of us, the parts just beneath the surface of our social mores fighting with our basest desires. These paintings lure as they terrify, inciting a reluctant humor.

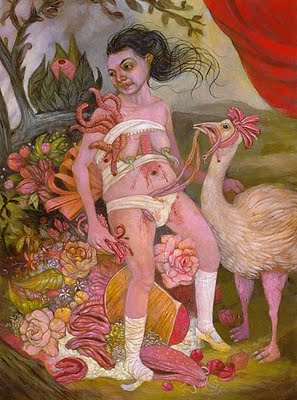

Many of his paintings are still-life oil paintings gone mad. In “Oozing Embankment,” from 2009, it is as if there was once a less subversive still-life there, the fruits representing anticipated consumption. But tradition has been turned inside out, upside down, and left to show us what is really there: color, decay, and a natural, oozing beauty.

Jacobsen’s paintings and performances conjure conflicted feelings of terrorized fascination, a beauty in decay and gore, the truth of human existence. These moments originate from the underbelly of desire, terror, instincts for consumption, and compulsions toward what is odd and beautiful.

Jacobsen grew up in Middlesex, New Jersey. “A very strange place with an inferiority complex,” he says. “It’s New York’s little neighbor with fading mobster guys who are really always shit on and are considered second tier.” He says that New Jersey influences him; its inferiority complex causes him to look inward to evaluate himself, his body, and then outward to reveal similar truths about others.

There is a thread throughout his paintings and performances that turns the body inside out. In Jacobsen’s work, we see the insides of things, and sometimes they are familiar and beautiful — sometimes they just simply evoke disgust. “I have had a lifelong fascination with the failure of my body,” he says. “Shit that comes out of my body — changes of my body — has always been fascinating to me and slightly horrifying.”

And almost always, food is involved.

In “Triumphant Aeronautics,” a figure is in the throes of something wholly indiscernible, but the action implies orgasmic pleasure in consumption and excretion. The figure may be on a stage or a table; both send the message of the primal inability to contain oneself. It shows violence right alongside uneasy, slapstick, melancholy humor.

Over quickly cooling coffee, Jacobsen goes on to discuss his paintings, as well as his Paul McCarthy-esque performances that play with notions of the body. He has not performed for a couple of years, in part because of the time and money his theatrical shows and music require.

The use of food in these performances signals the consumption and allure of the body. And, although one may see the influence of McCarthy, Jacobsen’s performances are very much individual to him. They are creations that only an an intense individual like Jacobsen could summon, peppered with free associations that are part psychological, historical, and anthropological, and definitely filled with an attractive set of emotions.

There is Otto Dix in Jacobsen’s raw play with the body, forcing its form to contort and challenge the viewer. Neo Rauch is there in the sarcastic, apocalyptic mood; whether it mourns for or laughs at the decay around all of us, one cannot be certain.

“I’ve been trying to paint like Lucien Freud, but that’s impossible,” Jacobsen says. “Though it has taught me a lot about mask, and trying to do that has brought me to another place. Some unconscious influences would be Jim Nutt, Otto Dix, and Barnaby Whitfield. And when I go in these directions, I am like, ‘Shit, this looks like a Barnaby Whitfield,’ or, ‘Shit, this looks like an Otto Dix.’”

His earlier work, though lush with foodstuffs and feedbags, is more traditional, and not filled with Freud’s shininess and masking. “Lady Bird” looks as if it is a strange and lovely abbreviation of Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus.” In Jacobsen’s work, the worship is not for Venus, but the carnal voracity that both the subject and its surrounding environment display.

Jacobsen says that his process involves free association, but that it is not the product of linearity or narrative. He explains, “Maybe a figurative painting would progress where I have an expression on a character, and that informs the posture and the body. Sometimes I will throw another figure in there, and then I will take out the other figure.” In addition to this, he has begun to sketch again, and he believes that it has helped his process become less arduous, especially with a deadline looming.

Jacobsen has been invited to have a solo show in Berlin at the Bongoût Gallery in April. “They started out doing silkscreens for rock concerts and art in France,” he says, “and then they started making a quarterly book of more transgressive European artists and some American artists — figurative work that is dealing with the body.” Jacobsen is included in one of these monographs.

There is modest excitement in him when he talks about the show, but also nervousness. With the deadline comes fear. After a yawn and a sigh, he says, “Then I have to make my way to Germany, which is very scary for me.” He admitted to a fear of flying that is rooted in anticipation. It’s a reticence that dissipates once he’s in the clouds, as if the murkiness of the sky is more comforting than the world on the ground.