World in Stereo examines classic and modern world music while striving for a greater appreciation of other cultures.

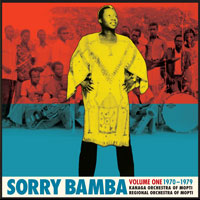

Sorry Bamba: Volume One 1970-1979 (Thrill Jockey, 6/19/11)

Sorry Bamba: Volume One 1970-1979 (Thrill Jockey, 6/19/11)

Sorry Bamba: “Porry”

[audio:https://alarm-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/07-Porry.mp3|titles=Sorry Bamba: “Porry”]Thrill Jockey continues its foray into the world-music scene with a collection of tunes from one of West Africa’s forgotten figures, Sorry Bamba. A father figure to the many musicians who came after him but somewhat unknown outside of Africa, Bamba’s music is another testament to the never-ending investigation of Mali’s rich musical history.

Born in Mopti, a city resting between Timbuktu and Ségou, Bamba plays a confluence of styles that stem from the region’s folk traditions. He’s best known for his powerful sing-talk vocals that can withstand the grittiest Afro-funk, electric instrumentation.

But this compilation, covering a mere decade of the artist’s half-century-long career, is more than ’70s Afro-funk. Bamba’s career in the ’70s was at a crossroads, a time characterized by Mali’s independence from France a decade earlier. While the country promoted modernization and celebration of Malian culture, Radio Mali sought for a push of musical heritage. Bamba was one of the artists at the forefront as the band leader for the Regional Orchestra of Mopti. In addition to funky fuzz, the collection shows hints of Malian blues, American soul, and Latin rhythms among Bamba’s take on regional sounds, most particularly the folkloric songs of the nearby Dogon people.

For those of us looking from the outside in, Mali’s Dogon villages, located in the cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment near Mopti, come to symbolize what is remote and tribal to Africa. Open the album’s gatefold, and you’ll see a photo of Bamba surrounded by the Dogon people, their bright tribal garb conservative compared to their intense wooden masks. Before the culture became a divergent attraction for tourists and anthropologists, Bamba was one of the first outsiders welcomed into the isolated society in the early ’70s.

Though the fierce tribal rhythms of Dogon music can be heard throughout the record, it’s most noticeable on “Sayouwé,” one of the livelier tracks on the album. Expressing honor for his ancestors, Bamba builds on the rhythms with a spacey synthesizer and an energetic horn section, with his sing-talk vocals given driving force by a female vocalist. By the 1980s, the Regional Orchestra of Mopti became known as the Kanaga Orchestra, a name symbolizing the god Amma, creator of the Dogon people.

Bamba’s work with the Dogons complemented his reign as band leader. Though collectives like the Orchestra of Mopti have been overlooked because of some of the period’s bigger names, such as Bamako’s legendary Super Rail Band, it’s easy to forget that there were many regional groups who played an electrifying fusion of griot music and regional music. Volume One 1970-1979 widens the scope of that scene, helping listeners to better grasp the music.

All of the songs were written and played by the Regional and Kanaga Orchestras with instruments ranging from organs and horns to the Western drum kit and the toumba and taamani. “Yayoroba,” Bamba’s biggest hit that was written for the Mopti Orchestra in 1974, draws on a crisp electric guitar and rhythmic keyboard melody, showcasing the group’s innovative stance on the African sound. “Porry” has a distinct, tripped-out groove with an organ and horn arrangement that could be easy inspiration for The Budos Band. The song begins with a dynamic, syncopated, guitar-and-bass riff, and Bamba delivers its trumpet solos with control and ease, commanding the melody into the rhythm with every blow of his horn.

Thrill Jockey has done everyone a great service by releasing this first volume from one of West Africa’s unheard voices. And as a collection of rare and never-before-released tracks, it must be noted that the project was overlooked by Bamba himself. Looking back, it’s easy to see why Bamba was so important as a musician and bandleader as well as a bridge between Africa and one of its most remote cultures. But the music can speak for itself. Sounds hinge on different influences but are ultimately African, envisioned and played honorably by Bamba and the pioneering musicians with which he surrounded himself.