Alec Longstreth: Phase 7

Alec Longstreth: Phase 7

The personal zine or “perzine” genre is one of the most popular in independent publishing (we’ve covered a few here, like EmiTown and King-Cat). It can be hard to distinguish yourself in such a crowded field, but Alec Longstreth’s Phase 7 stands out. Published by the author since 2002, Phase 7 is a series of minicomics, most recently alternating between five-issue adventure story “Basewood” and sketchbook issues on the artist’s life. It’s personal, funny, and, incredibly, quite original.

Despite its most recent form, Phase 7 is much more than “Basewood” and even departs frequently from personal stories. As Longstreth says, “The subject matter of each issue of Phase 7 varies widely, depending on what kind of stories I want to tell. I’ve done auto-bio, attempts at serious fiction, humor, comics essays, stick-figure diary comics, and sketchbook issues.” Variety is the key to Longstreth’s longevity, but it also seems like the outgrowth of a natural impulse to continue experimenting and learning.

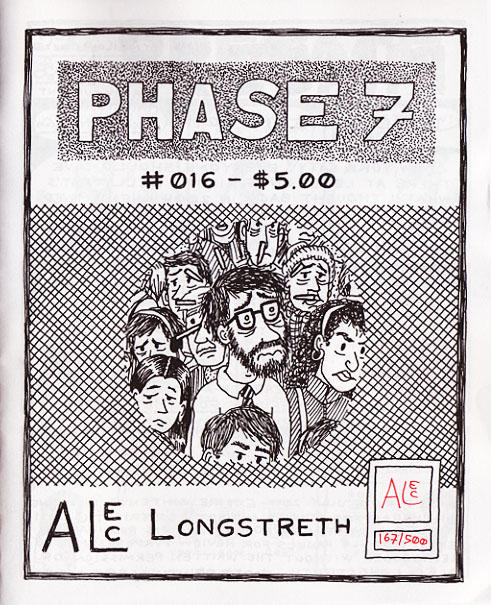

Issue #16 in particular covers Longstreth’s years in New York, struggling to make a living and forget old loves while pursuing new ones. He also includes plenty of absurd and charming interactions with New Yorkers on the subway or in parks. Random denizens of the city approach him to offer encouragement on his drawing, or simply to yell at him. We see Longstreth at work, out with friends, on dates, and in a wide variety of ways, adjusting to life in New York.

Most of Longstreth’s artwork is miniscule (the panels are usually one-inch squares); his drawing style is appropriately simple but expressive. Some of these comics are particularly rough, given the original sketchbook context, but undeniably interesting.

For Longstreth, art and cartooning is a process of evolution. His interest in experimentation comes through even in the sketchbook issue; some panels are ornate, while others are little more than scribbles, and his page format changes frequently. Longstreth says of his drawing technique, “I was doing a lot of theater work before I started making my own comics, so I definitely think about choosing a specific drawing style for each story, the same way the set, costume, and lighting designers will design a specific look and feel for each play.” His interest in playing with form is especially noticeable in a flow-chart page that shows his future; abortive options circle around each other, conveying uncertainty.

Although the sketchbook issue was apparently meant to be a placeholder when gaps between “Basewood” issues became too large (Longstreth describes them as something “quick and fun” to work on during Basewood issues), it stands on its own as a nice addition to the perzine genre. It’s impressively polished but never really lets you forget its self-published roots. Longstreth views his role as publisher as privileged, in that it allows him to preserve his own voice in a way that mass media can’t compete with. He adds, “No one makes any money self-publishing mini-comics, so it is usually done purely for the love of the art form.”

Now that he’s finished with the “Basewood” story, upcoming issues of Phase 7 will focus on the band Weezer and movies from Longstreth’s childhood. There’s a sense of play in Phase 7; new issues could be about anything, and it’s interesting to see what the author chooses next.