Monotonix is on its fifth American tour, says singer Ami Shalev in his thick Israeli accent. He can’t say that anything specifically odd has happened on this stretch of dates; it’s not like the last 65-show tour when the three-year-old band met up with the Fucking Champs’ Tim Green in California to record one song that turned into Monotonix’s six-song EP Body Language. On that tour, the trio spent three days traveling from the studio to perform around California and visit musical friend and band idol Ayal Nistor. The band was already 40 stops into the jaunt when it went into the recording studio.

The oddest part of this tour is not really odd at all; it’s just something Shalev noticed while playing post-Katrina New Orleans. “When we’re driving, we’re always looking for the cheapest gas,” he begins. “So we see that this one sign is $1.00 a gallon. We say, ‘All right, we’re going to fill up the car. We’re going to fill up everything: water bottles, tank, everything.’ We drive up to the gas station, and it looked like it hadn’t been open in three years—trash everywhere. It looked like a Mad Max scene.”

When Shalev recounts the details, he often pauses for story effect. But one also gets the sense that he is being careful to not offend anyone. On stage, Shalev does everything he can to excite a crowd. In fact, he’s often caught in photographs midstage dive and drenched in fans’ beers. Off stage, Shalev is reserved and cautious.

“You can’t make or do music in Israel without being touched by some other kind of music. That’s the reason why everything doesn’t have its own direction. Right now, people are beginning to understand that you have to do it in your way.”

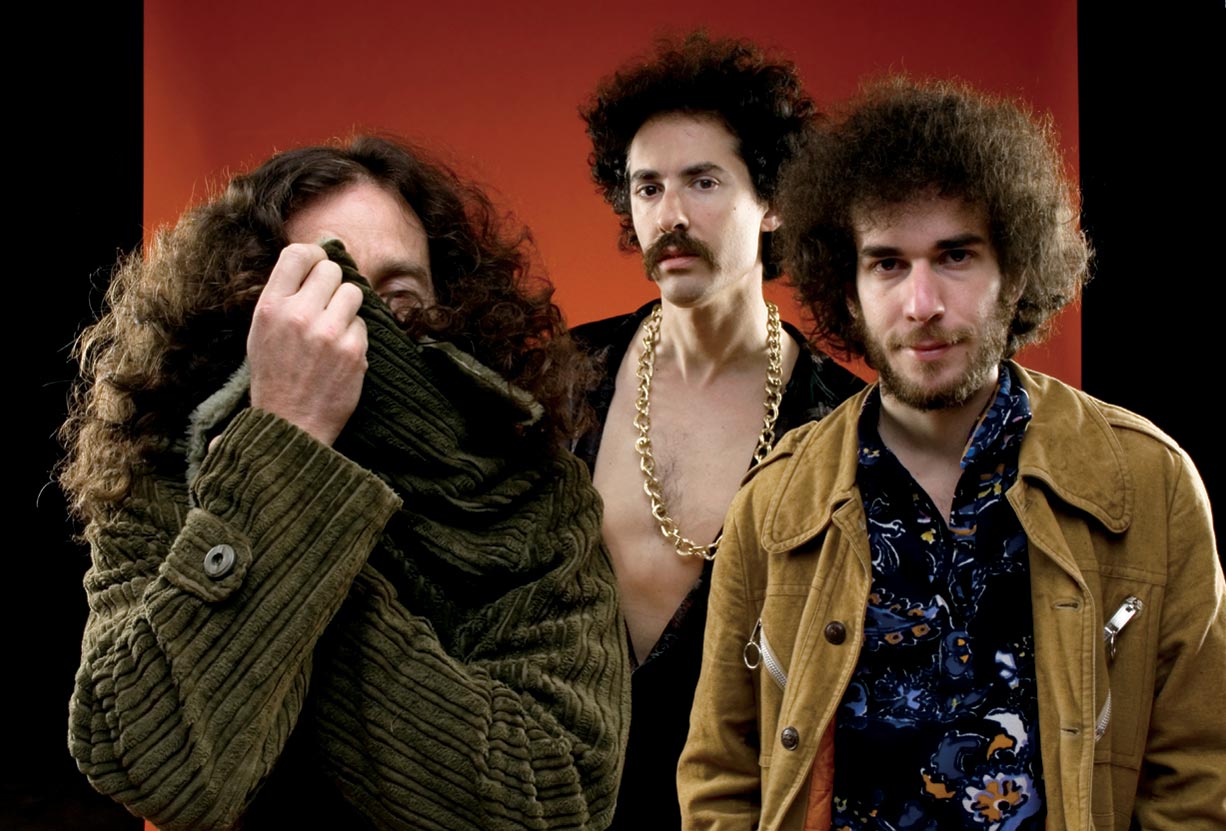

The last thing Monotonix wants to be is known as “that Israeli band.” Aside from their visceral, hedonistic live shows—wherein Monotonix members have been known to leap into crowds, hang from ceiling rafters, moon audiences, and dump full garbage cans over their heads—their nationality is the most talked-about aspect among American fans, but the one they are least likely to bring up in conversation. Responses must be obtained through a circuitous route before ending on the question of whether or not Israel is, indeed, metal Mecca, as it’s often portrayed.

“I don’t think the metal scene is relatively big. It’s just a metal scene,” guitarist Yonatan Gat says.

“But there is a metal scene,” drummer Haggai “Gever” Fershtman adds.

“Compared to the mainstream scene, it’s not so big,” Shalev interjects. “But compared to the indie-rock scene, it’s bigger.”

The trio’s native city, Tel Aviv, is the second largest in Israel. With a population roughly the size of Provo, Utah, a penchant for modern art, and a technology-refurbished economy, it’s considered the country’s cultural capitol. These elements would seem to aid collaborations between musicians both in Tel Aviv and across what is often seen as a difficult-to-cross American pop culture border. But few Tel Aviv, let alone Israeli, bands have achieved the level of Western attention, or perhaps notoriety, that Monotonix has received. The trouble may be most Americans’ limited knowledge and support of non-Western rock bands, but it may also be the lack of supportive infrastructure within Israel for rock bands like Monotonix.

“In Israel, because the scene is so small—nobody can go anywhere—and it’s very secluded, geographically and culturally, people are less supportive of each other,” Gat says. “It’s a more competitive situation. But it’s been getting better. People are becoming more aware of what’s going on in the outside world, how small the scene is, and what needs to be done in order to get good bands out there and get a good scene going.” Though optimistic, when Gat refers to things getting better, he specifies with modifying phrases like “in the past five years.”

A lot has happened in the last five years in the Israeli indie music scene, including Monotonix favorite My Second Surprise (an Ayal Nistor project) receiving MTV video play and making an appearance at 2007’s SXSW and the rise of cross-genre bands like Tel Aviv’s The Genders.

Occurrences like this not only seeded the ground for a band like Monotonix, but also for Shalev’s prior project as vocalist for noise-rock trio Mono Addicted Acid Man (with first Monotonix drummer Ran Shimoni, who was known for his pyrotechnical stunts on previous Monotonix tours), Fershtman’s coinciding project as drummer for indie rock trio Ex Lion Tamer (he’s also a trained jazz and African drummer who is often referred to as the “hardest working drummer in Israel”), and Gat’s previous work as bassist for Israeli punk band Punkache and present solo work as an acoustic singer-songwriter. Nevertheless, supportive audiences, venues, and recognition didn’t come until these bands toured outside of Israel, as many Israeli bands attested at the 2006 CMJ showcase.

“The mainstream, the indie — it’s all mixed together,” Shalev says. “It’s not separated. You can’t make or do music in Israel without being touched by some other kind of music. That’s the reason why everything doesn’t have its own direction. Right now, people are beginning to understand that you have to do it in your way.”

“There’s also this thing where, in Israel, if you sing in Hebrew you’re more likely to get attention from the media.” Fershtman adds. “If you sing in English, you’re going to stay unknown, because the media doesn’t support English bands.”

Gat agrees, adding, “If you sing in English, people will frown upon you in a way, and there will be less of a chance that you’ll be played on radio. But we were never interested in getting to Israeli media. Our kind of music will never get there. Israeli radio is kind of soft rock.”

However dominant Hebrew pop radio is perceived to be by the Israeli indie music scene, all three members note that the cultural differences are deeper than just available venues and other supportive band structures. There’s also the issue of music sensibilities. Monotonix are heavy on guitar solos, driving beats, and noise rock-influenced vocals. Their sound has been labeled everything from classic rock revival to gutter-garage. Monotonix is comfortable with the label of performance art rock band, a genre that may be perceived as idiosyncratic to the majority of Israelis, particularly because of Monotonix’s emphasis on what the band says are its “party” sentiments.

“It’s kind of weird,” Gat says. “Israeli mentality is very open and loud, but the music they like is very sad minor-key songs, like the suffering of the Jews or something—I’m just kidding, but you get my drift.”

“It’s not a joke,” Shalev adds. “In Israel, our music doesn’t fit the mentality—and I’m being serious right now—people in Israel don’t have the tradition of getting a real party [together]. People in Israel get a party together just to run away from things. Israel is…a mellow country.”

“Did you say ‘mellow country’?” Gat asks. “But if you go to bars and stuff, it’s pretty crazy.”

“Like trance parties,” Fershtman interjects.

“But it’s not a way of life,” Shalev argues. “It’s more like escapism. In Israel, music is escapism.”

“Rock music is escapism,” Gat counters, adding, “For Israelis— I’m talking about the mentality; I’m not trying to generalize—sad songs about heartbreak or suffering, that’s all people like to hear. It’s very different from [the United States]. I once heard an interview with someone—I don’t remember who, someone from an American band talking about a single from his band not making it—and he said, ‘Yeah, they told me to choose an upbeat song. But I had to choose this sad song, because I liked it.’ In Israel it’s just the complete opposite. If you want people to like your song, it would be better if you like a sad song or a quiet song.”

This predilection is one of the many reasons why Monotonix looks forward to performing and playing its shows abroad. Many Israeli rock bands have noted that the availability of performance venues, the faster exchange of information, and the larger audience base are elements to make touring the United States a band necessity, despite the long process of visa applications and the red tape some bands encounter once they arrive.

Monotonix’s live-show enthusiasm also elicits an audience response that isn’t often accessible in Israel’s indie music scene. The excitability factor of American audiences is particularly something they always take away from touring the United States.

“We just want people to feel free and let go and do whatever they want,” Gat says. “In the beginning, when we played in front of nobody or we played in front of five people, we could run around the room and do whatever. But now we get to some places that when we get there—even before we play—we feel that people really want to go crazy. The audience is already going insane for us. We just have to stand there and give the energy and play our songs.”