Hear the word “community” and what comes to mind is a cloying picture of clasped hands or multihued, smiling children. The word smacks of meaningless, feel-good phrases about commitment. This image of “cuddly community,” as its termed by artist, educator, and activist Christian Nold, is impotent and non-threatening; engaging it involves no real concessions or consequences.”Real communities tend to have many issues both externally and internally,” says Nold. “They don’t tend to follow the corporate image of an Asian, a European, a black person, and an American holding hands, smiling.”

This slick, toothless message is the antithesis of Nold’s adventurous work constructing and deconstructing language, technology, and the communities they affect.

The German-born Nold is dedicated to researching forms of social control, uses of technology, language, and media, and the dynamics of public spaces. He then uses that heady research to produce accessible and socially constructive, community-enhancing tools that change the balance of power. Innovative projects with high-tech names like Bio Mapping, the Crowd Compiler, and the Affect Browser.

Nold began his career studying Fine Art at Kingston University in England (where he currently resides). At the same time that Nold was studying video art and new media and meeting inspirations like British net artist Heath Bunting, he was learning first hand about the risks of art and activism in public spaces.

“I was going to lots of demonstrations and starting seeing things first hand,” Nold explains. “I felt politicized by seeing the violence of the police and the bizarre tactics they were using.

What Nold witnessed was surprising. Techniques like containment and dispersal, generally understood to be non-violent tools for keeping order, were used instead to aggravate and spread panic. This sense of panic, of unruliness and danger, drives most average people away from protests. The few that stay are radicalized, sometimes embittered, and often inhabit the fringes of their movements. Thus peaceful democratic protests become the provenance of “extremists,” alienating the mainstream and supporting the media’s image of protestors as weirdos. Spreading panic is key to this complicated system of marginalization and coercion.

What Nold witnessed was surprising. Techniques like containment and dispersal, generally understood to be non-violent tools for keeping order, were used instead to aggravate and spread panic. This sense of panic, of unruliness and danger, drives most average people away from protests. The few that stay are radicalized, sometimes embittered, and often inhabit the fringes of their movements. Thus peaceful democratic protests become the provenance of “extremists,” alienating the mainstream and supporting the media’s image of protestors as weirdos. Spreading panic is key to this complicated system of marginalization and coercion.

“My feeling is that the police are about intimidation,” he says.

“They can’t use very real violence so it is all about threats. I realized that so much is about display. The uniforms and tactics are a form of psychological warfare.”

Architecture is the skeleton upon which experience happens, but people are more into fl irting than looking at buildings.

After graduating from Kingston, Nold spent an unhappy year in web design before non-profit book publisher Book Works approached the artist about his BA thesis on riot police and crowd control. The organization was interested in Nold’s “autonomous protest tools” (for example, helium balloons that drew attention to obscured CCTV cameras). The resulting book, Mobile Vulgus, is the result of a year of independent reading and research with crowd psychologists, activists, riot police, and non-lethal weapons manufacturers. But Nold found his research had broader applications than just protests and crowd control: “I started seeing these kind of systems everywhere-subtle systems of techno alienation.”

Nold earned his master’s degree in Interaction Design at the Royal College of Art, gathering the programming and electronics skills necessary to bring his conceptual tools into the real world. One of his fi rst tools was the Crowd Compiler.

The Crowd Compiler “makes visible the temporal crowd,” Nold explains. It is a fi xed camera mounted in a public place that takes 100 photos spaced out over regular time intervals. The resultant images are analyzed with software that compares the images pixel for pixel, looking for color differences. All these color changes are compiled into a single image documenting all the moving things that have passed by the camera’s lens during the course of the 100 photos.

“[The idea] came out of this demonstration in San Francisco,” he says, “where a newspaper had used photographs to decide the size of the demonstration but had ignored the idea of turn-over, of people coming and going.”

Unlike most representations of crowds, those from the Crowd Compiler do more than just quantify the crowd. They are graphic and easily understood examples of human dynamics, taking into account the fl ow of people through public spaces. Mapping people walking through a public square or shopping mall gives clues to the effect of architecture and design on group behavior. A viewer can see a now-empty thoroughfare haunted by the ghosts of everyone who has recently passed through it, and the images are as aesthetically intriguing as they are sociologically useful.

This inquiry into people and spaces would lead to Nold’s most famous project, creating “bio maps” of cities like London, San Francisco, and Bangalore.

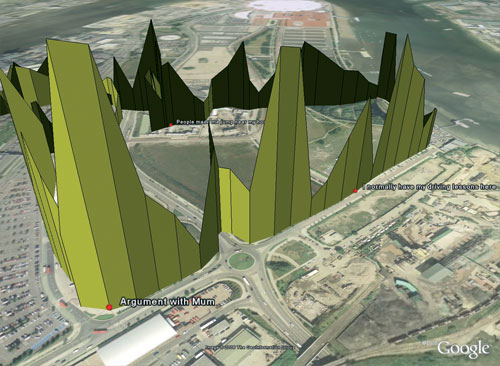

For this ongoing project, volunteers are asked to wander the streets of their cities while wearing a Galvanic Skin Response device akin to a lie detector. This detector measures their physiological responses to their surroundings-responses that can be annotated with comments like “Strange sound coming from basement” or “Here’s where I met Amy.” The results are compiled into an “emotional map” of the city.

Maps have long been used for social and political ends, yet modern maps retain an unearned aura of objective rationality. A city or country map appears devoid of human infl uence, is a static and rigidly defi ned grid of buildings and landscape features, and is a poor representation of lived space. Nold hearkens back to maps from the seventh century, when sketched human fi gures were a common addition to the landscape.

“I think it is interesting that in the past, people could be present on maps and it was not considered strange,” Nold says, because the social and physical bodies of the city are linked in obvious if not often articulated ways. There are no human-inhabited spaces that are not marked by experiences and memories, leaving behind ghost trails like the passersby on the Crowd Compiler.

In bio-mapping cities around the world, Nold found that emotional content was what most defi ned a volunteer’s reactions to his environment. Rigged with Galvanic Skin systems, people responded more strongly to interactions with one another than to architecture, design, or landscaping.

“Architecture is the skeleton upon which experience happens,” says Nold, “but people are more into fl irting than looking at buildings.”

In recent projects, Nold is expanding his own notion of community space, investigating language and discourse as his volunteers investigate the rocks, trees, sidewalks, and shopping plazas that make up their hometowns. The interaction of technology, public space, and public discourse is evident in his studies of RFID (radio-frequency identifi cation). RFID is an emergent technology that will allow businesses, governments, or individuals to insert tags into people or objects and then track them via radio transmissions.

This controversial technology could potentially be used in everything from supermarket packages to passports-for benefi cial purposes like tracking corporate toxic waste dumping as well as nefarious applications likened to “Big Brother.”

Because it’s so new, there is a lot of fear and not much clarity. Public opinion is shaped by the metaphors used to describe RFID tags-from the cheery “green tags” to the menacing “spy chips.” “I am interested in the language and metaphors that are emerging,” says Nold. He is now compiling a list of the metaphors in preparation for a new map.

“In itself, RFID is very dull. The metaphors give it power. If we can make social democratic metaphors, we will have a less oppressive technology.”

Nold hopes that by framing the conversation early, artists and activists can harness this technology for socially beneficial ends.

“Fear is the general currency around these topics,” says Nold. “I would like to substitute the fear discussions with a dialogue around agency [and] empowerment.”

The community-minded artist fears that misused RFID technology will erode public space. “I think lots more of our lives will be automated by systems-systems that open doors, lock them, or hide them. We may not know that for some people there is a door there. Depending on your RFID status, these doors may open or you may never know that it exists. I think the idea of a shared public space will disappear.”

During research and workshops, Nold has conscientiously avoided putting his own slant on the project, instead collating and displaying the thoughts and fears of the public. But when he is asked to imagine the likely future of RFID, he becomes wry. “I think it will be the usual mix of the banal and the oppressive,” and he adds, “with artists making it playful.”

It was while studying media coverage of RFID that Nold developed his Affect Browser. This software “reads” a website to uncover its sometimes-hidden emotional slant. The text appears as a series of word clouds: red for positive, blue for negative, and yellow for the ten most frequently used words.

“I think lots of this technology is being discussed in a very emotive way. By navigating the discussions via their emotive slanting, it helps to identify some of the key actors. Then you can see who is promoting certain ideas.”

Emotional slant is not new, of course, or specifi c to the internet, though bloggers may have upped the ante on effect-driven discourse. On his current project True Nature, Nold is partnering with digital media artist Ali Sant to scan texts on the Green movement and feed them through the Affect Browser. The pair is using open-access documents in the Prelinger Archive to trace texts from the beginning of the environmental movement to the present day, looking for semantic shifts that signal news way of thinking about the environment. Like the Crowd Compiler, Bio Mapping, or any of his dozens of other projects and interests, True Nature is a practical application of Nold’s inquiries into community, language, and technology.

“Technology is the world we swim in,” the artist concludes. “We use technology when we speak and write. It is everywhere; it is never neutral. But it can be used by people to change their world.”

– Summer Block

Christian Nold: www.softhook.com