Mike Patton: “Il Cielo In Una Stanza” (Gino Paoli)

[audio:https://alarm-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Mike_Patton_Il_Cielo_In_Una_Stanza.mp3|titles=Mike Patton: “Il Cielo In Una Stanza”]

Mike Patton: “Deep Down” (Ennio Morricone)

[audio:https://alarm-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Mike_Patton_Deep_Down.mp3|titles=Mike Patton: “Deep Down”]

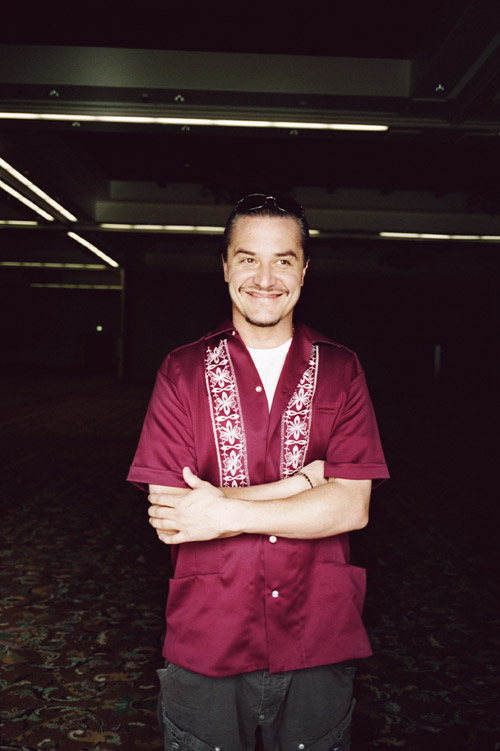

In 1994, the musical aberration known as Mike Patton prepared for a pair of life-altering experiences. The anomalous vocalist married Italy native Titi Zuccatosta, and the two purchased a home in Bologna — a city that Patton has since described as the “place where you want to die.”

Putting the personal ties aside, his infatuation with the city is easy to understand. At one time the “second city” of Italy, Bologna holds a rich and deep history. It is home to the oldest university in the West and an abundance of monuments that span the past two millennia. Visitors flock to Piazza Maggiore and the San Petronio Basilica, two symbols of a city renowned for its expansive porticos and the red roofs of its historic center. Its humid climate makes seasonal swings feel more extreme, but given Bologna’s location in Northern Italy, its inhabitants aren’t as hard hit by heat waves as the south of the country. And Bologna is, naturally, a culinary hotspot thanks to its famous Bolognese sauce.

Though the couple separated in 2001, Patton had, by that time, immersed himself in the country and its culture, refusing to speak English while abroad in order to become fluent in Italian. Every day was a learning experience, he says, and his most important education came in linguistics.

“Being ‘invisible’ or in disguise helped me learn the language,” Patton says. “The great thing about Italy [is that] if you just say two words, like ‘ciao bello,’ [they say], ‘Wow, that’s amazing! You sound just like an Italian!’ It really boosts your confidence. The whole attitude [in Italy is] toward acceptance and tolerance. The reason that I learned the language and did it so fast…is because the people were so amazing.”

“In the early stages [of working with the orchestra], I’d fly off the handle and go crazy, and it got me nowhere. Orchestra people don’t want to see that, don’t want to hear that. They already think you’re a freak for doing this.”

The thought of Patton concealing himself, however, seems like a non sequitur. His voice, after all, is one of the preeminent and most recognizable in independent music. It has been involved in dozens of personal projects, invited on scores of guest spots, and heard on more than a hundred studio recordings. His malleable voice is known for any combination of dramatic cries, harrowing screams, smooth croons, lilting falsettos, and otherworldly chants.

Patton’s days fronting alt-rock favorites Faith No More were a gateway drug for many, leading first to the mind-altering, genre-demolishing tastes of Mr. Bungle. Then came dalliances with John Zorn, arrangements for Fantômas, time in Tomahawk, pop adventures as Peeping Tom, and copious collaborations. His time on the radio all but ended after Faith No More’s breakup, but his distinct sounds and diverse palette — coupled with a reputation for stage antics and off-the-cuff interviews — cemented his place in modern music lore.

So given these identifiable attributes, the words “Patton” and “incognito” don’t seem to follow each other. But his newest project, Mondo Cane, stems from just such a union — with Patton disguising his American accent and assimilating to a new culture.

“I did have a lot of friends there,” he says of Italy. “Most of them spoke English, but my whole deal was ‘don’t speak to me in English; I have to learn.’ I’m not doing any DVD Rosetta Stone bullshit. Trial by fire, you know?”

Yet Patton learned more than Italian. His interest in Italian counterculture led him to figures like Demetrio Stratos, a 1970s prog-rock revolutionary who explored the limits of the human voice. He later met, befriended, and collaborated with modern musicians, including Zu, a Roman avant-garde trio whose recent sludge-jazz album was released via Patton’s Ipecac Recordings.

But despite his affinity for these kindred artists, Patton found himself drawn to the lavish, layered Italian pop music of the 1960s that he had encountered through friends and the radio. (He is, in the end, an artist whose catalog appeals as much to casual listeners as to ardent experimentalists — an artist as likely to sing with Norah Jones as Melt-Banana.) At some point, it became obvious to him that he’d pay tribute to these expansive orchestrations, and the Mondo Cane project was born.

In the years after World War II, American pop influence began permeating the globe, and the Italian Republic quickly embraced bebop, big band, and rock and roll. By the late 1950s, Italian singer-songwriters — known as cantautori — had come to prominence, at first influenced by Italian folk but then drawing inspiration from traditional American pop singers. As the ’60s progressed, cantautori appropriated bits of rock, psychedelia, and film-score dramatics, culminating in a heavily layered style that just as readily embraced guitars as string sections.

It was this dense, intelligent take on pop that attracted Patton. Legendary composers of the time, both in Europe and the USA, had begun writing and arranging for singer-songwriters, either out of artistic interest or for financial gain (or both). Prominent cantautori such as Gianni Mecca, Gino Paoli, and Luigi Tenco were working with names like Ennio Morricone, Nino Rota, and Tony De Vita.

Others recorded their own Italian-language renditions of famous pieces by American or European composers such as Elmer Bernstein or Bert Kaempfert, who worked with some of the most recognized singers of the time.

One such tune, originally titled “The World We Knew (Over and Over),” exemplifies the cultural difference and the impact that it had on Patton. Renamed “Ore D’Amore,” this selection — which would be appropriated by Mondo Cane — was first sung by a vocal giant.

“Sinatra did that song!” Patton says. “But it’s completely different. It’s much more lush and big bandy and orchestral. For whatever reason, the Italian version was much more fuzzed out and ’70s and psychedelic — totally different words, totally different everything. Somehow, I feel, a lot of these [reinterpreted] tunes were given an Italian soul. They’re much more tragic, much more romantic, and much more exaggerated, and that’s definitely something that interested me.”

With a growing catalog of tunes in mind, Patton contemplated a few one-off cover performances with a quartet. However, when a festival promoter called and offered access to an orchestra for three concerts, he couldn’t say no. He began sifting through hundreds of pop songs — many that perched atop the charts but some with more obscure origins — and the wheels were in motion for Mondo Cane.

Loosely translating to “dog’s world,” Mondo Cane was a massive undertaking, consuming months and months just to prepare for the initial three performances. Patton had his selections transcribed and began working with a 10-piece band, while a conductor was put in charge of a 40-piece orchestra.

There were no initial plans for the dozens of concerts that would follow, nor plans to record an album — but at some point, Patton figured that this effort warranted documentation. Italian producer/composer Daniele Luppi came on board for arrangements, and over three new concerts in 2008, the group took part in live recordings that would be assembled into the first of two Mondo Cane albums, released in May of 2010.

“That led me down, let’s just say, another vortex of getting it perfect,” Patton says. “Hey, it’s a live concert, and I hate live-concert recordings. I just can’t listen to them; I can’t deal with it. It took me a long time to correct all the mistakes and redo the arrangements, maybe the way I really wanted them and heard them in my head from the beginning but didn’t have time to execute for the concerts.”

The performances, many of them in public squares, were a success by all accounts, but the entire process proved overwhelming at times.

”There were times when I wanted to tear my hair out,” Patton says, “because you feel like, ‘Who’s helping me? Who’s got my back?’ I thought of this [project]; Jesus Christ, I guess it’s all my responsibility! It was definitely a huge learning period for me, and you have to learn where to pick your battles, when to be a politician, and all that kind of stuff. In the early stages, I’d fly off the handle and go crazy, and it got me nowhere. Orchestra people don’t want to see that, don’t want to hear that. They already think you’re a freak for doing this.”

A few “offbeat” inclusions made Patton unsure of how the project would be received in Italy, particularly in front of mixed crowds at the piazza performances. But despite the unconventionality of the project, the selections on Mondo Cane are, by and large, approachable, appealing to Patton lovers as well as their parents.

“I remember one sound-checking [when] we were playing one of these gigs in an outdoor square,” Patton says. “We were sound checking between songs, and an old lady comes up toward the stage. [She said], ‘Excuse me; excuse me. You know, you have a fabulous voice, son. Is there anywhere that I can buy your cassette?’ I was just so touched. That was total validation for me.”

why do you call yourself mike and not brent? your an ass!