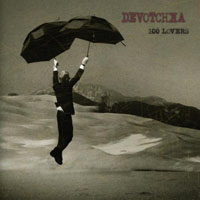

DeVotchKa: 100 Lovers (Anti-, 3/1/11)

DeVotchKa: 100 Lovers (Anti-, 3/1/11)

DeVotchKa: “100 Other Lovers”

[audio:https://alarm-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/DeVotchKa-100-Other-Lovers.mp3|titles=DeVotchKa: “100 Other Lovers”]Nick Urata very much is a kid — prone to theatrics, fascinated by time travel, good at nearly everything he does but still humble, as if he doesn’t yet know how to be arrogant. But Urata is increasingly faced with grown-up responsibilities as one of Hollywood’s go-to composers and a member of label-defying Denver quartet DeVotchKa.

Fortunately, the frontman is also a seasoned musical veteran. Urata grew up in New York City, part of a Sicilian immigrant family full of musicians. He lived and busked in Cicero, a Chicago village also populated by immigrants, before moving to Denver, where he finally pieced together DeVotchKa. Accompanied by violin and accordion virtuoso Tom Hagerman, bass player and Sousaphonist Jeanie Schroder, and drummer Shawn King, Urata fills in the eclectic mix with guitar, trumpet, piano, and Theremin.

The band found a tipping point with its Oscar-winning soundtrack for Little Miss Sunshine in 2006. Scored by DeVotchKa and Mychael Danna, the film didn’t so much open doors for the band as it opened windows — all of the windows in the house, letting the world hear the wondrously exotic and melancholy sounds that the musicians had been making all along.

Five years later, the band is poised to release its latest album, 100 Lovers, on Anti-, set to drop March 1. In addition, Urata has added a few more films to his repertoire, the most recent of which is I Love You Phillip Morris, the story of a gay con man (Jim Carrey) trying to spring the love of his life (Ewan McGregor) from prison.

For Urata’s childlike soul, though, a growing list of responsibilities can be grueling. “Films are very demanding, and you must write, write, write,” Urata says, admitting that the sheer amount of creativity he burned through while writing under deadline was, in fact, vital for the new record.

“A lot of these songs were things I wrote for films that got rejected,” he says of the tunes on 100 Lovers, “or were born because I was chained to my desk and couldn’t go to the bar. As painful and isolating as it can be, it can result in directions you never would have gone.”

Directions, plural — an accurate assessment of 100 Lovers. Listening through, it’s a bit of a Tilt-A-Whirl: rising, falling, spinning ’round, a new vector every track. Yet you’re not throwing up — a testament to the band’s musical prowess.

“A lot of these songs were things I wrote for films that got rejected, or were born because I was chained to my desk and couldn’t go to the bar. As painful and isolating as it can be, it can result in directions you never would have gone.”

DeVotchKa’s penchant for vintage equipment meant that some new directions were unplanned: “We used a lot of old tape delays,” Urata says, “and the fact that they were kind of broken made for some moments we could never duplicate in a million years.”

The always dapper, GQ-meets-Bohemia frontman opts out of “captain” responsibilities when it comes to the band. Urata describes himself instead as a kind of helmsman / lookout, running back and forth from the crow’s nest to the ship’s wheel. “My role has always been to steer the ship — and yell stuff when we’re about run into the rocks,” he says. Of course, it’s also his job to write the words, and though DeVotchKa’s musical philosophy is one of indiscriminate openness, its linguistic approach is fairly restricted, concerned mostly with the subjects of love and loss. Note the album title.

When asked about his writing, Urata, perhaps predictably, says that he reads a lot of poetry. “All the great writers and musicians say their best stuff has been beamed to them from some benevolent keeper of the collective unconscious,” he says. “I’ve had it happen a few times in my humble existence. You never know if it’s going to happen again, but with great poets you can see it happening on the page in front of you, and that’s why your eyes well up.

“I got turned on to Rainer Rilke a couple of years back,” he continues, “and…he’s really comforting, because in the most eloquent way he lays it out: we are all fucking bat-shit crazy, and love makes you even crazier.”

Early detractors said that Urata was crazy. Few in the mid-’90s thought that adding a tuba to a rock-and-roll band was a good idea. It turned out that it was, and now 100 Lovers upholds this adventurous audacity. “You always hope to expand and discover new territory,” Urata says. “There were a few songs that might have gotten thrown out with the bath water because of over-thinking, but we followed our gut and kept digging, and the results were really exciting to work on. At this point, we look at [an album] as a large empty space that we have to fill with something that will entertain the listener. Anything that can fill the void in an interesting way is welcomed with open arms.”

Anything means anything. As a jumping-off point, the new songs use the vibrant array of musical styles on 2007 album A Mad and Faithful Telling. With a less overt gypsy sound — despite a recent tour with Gogol Bordello — the band welcomes new friends into the family. Musically: ’80s new wave, African influences, grungy electric guitar, a children’s choir. And literally: several members of Calexico, as well as Mauro Refosco, who plays regularly with David Byrne and Thom Yorke’s Atoms for Peace. “We met Mauro when we toured with David Byrne,” Urata recalls. “We were in awe of his playing, and we became friends and always bugged him to play with us. That’s him playing most of the percussion on the record.”

What holds this pastiche together is where DeVotchKa didn’t depart from its charted course. Once again, the band returned to Craig Schumacher at Wavelab Studios in Tucson, Arizona. “The desert is still very exotic to me, a New York kid,” Urata says. “It always brings us back to a very romantic time when our band was taking its first baby steps and a room of ten people was a fucking event.

“Wavelab is in a section of town in a building that is frozen in time,” he continues. “The studio is piled with vintage gear, and there have been a few times when I was alone in there that I really started to feel like I had traveled back in time — it was just a hallucination, but it was so comforting.”

Moments of comfort were to be enjoyed while they lasted. As DeVotchKa endured the tedium necessary to bring the album to fruition, the exhilaration of discovery was tempered by a feeling of loss.

“The thing that sucks about working on albums and films is you spend so much time tinkering with them that you can’t enjoy them as art ever again,” Urata says. “So I suppose for us, the one window is right when you start mixing—the album never sounds that good again.”

The band isn’t back to where it started though. The album is a record of its travels, its discoveries, and, most of all, its perseverance. “We should have called this record ‘Doubt,’” he says. “We had all these songs that we couldn’t finish for like two years. Every time I thought I had a good lyric, the next day it would seem ridiculous. But we pressed on, and all our wheel spinning and false starts actually led to the songs developing into something that would have never happened if things went smoothly.”