Imaad Wasif and Two-Part Beast, a Los Angeles band formed in 2006, have self-released a record that is unusual in its maturity and clarity. It feels like a living thing for all the rawness and unabashed spiritualism displayed in its ten songs. Strange Hexes is a rock album. Bobb Bruno plays bass and keyboards; Adam Garcia plays drums; Wasif plays guitarist and sings ably. But it is also much more.

Lonely, muted electric guitars begin “Wanderlusting,” which quickly segues into a solid groove steeped in folksy minimalism. Wasif’s voice, tender and shaking, intones lines like “The color of gold scarabs in magnetic fields/on the rails” as if he’s in a trance; drums and distortion build steadily behind his androgynous wails.

Stylistically, Wasif and Two-Part Beast owe a lot to Led Zeppelin, T. Rex, and other early ‘70s groups for whom mysticism and rock music are intertwined. He is heavily influenced by Television guitarist Tom Verlaine; the two share a talent for off-kilter solos that are unconventional and distinctive enough to stand as their own instrumental songs.

Tunes like “Unveiling” contain lyrics that are a repeated themes on Strange Hexes: namely, the singer’s feelings of spiritual disconnection and an earnest desire to communicate and connect.“Symbols that I see as vows of secrecy/I have roamed the midnights as a visitor,” Wasif drones in an almost falsetto delivery. By the time he sings of feeling “so fucked up in the corner,” there’s little question of the man’s intent.

“I feel mutilated by the business aspect of making music.”

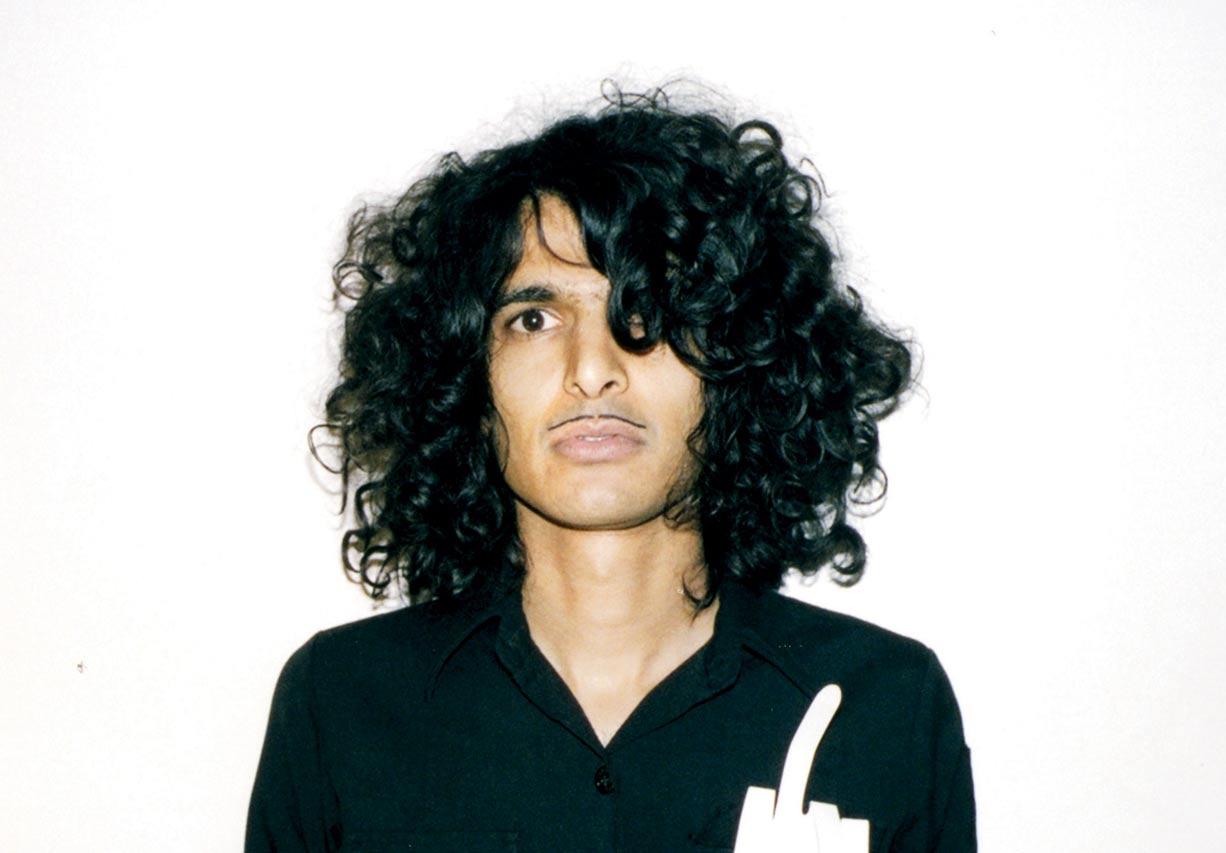

Despite Strange Hexes’ downcast lyrics, it is also intensely sensual. Wasif’s voice wavers effeminately, juxtaposed against the distorted guitars and heavy-handed accompaniment by Bruno and Garcia. It doesn’t hurt that Wasif is young and good-looking, fragile and intellectual.

Wasif is 32 years old. He began writing songs at 14, and made the career decision to follow music indefinitely. It fit his background. Wasif’s parents are artists who sought inspiration around the world. Wasif was born in Vancouver, and grew up in India (his parents’ home country), Los Angeles, Palm Desert, and San Francisco.

“It seems like each move was in search further isolation,” Wasif says of his father. “He moved to the desert to be away from people.”

For all Wasif’s songs about alienation, he is connected, geographically anyway, to 3,600,000 people. He’s talking via cell phone from an abandoned building in Los Angeles, a city of 3,600,000 where he lives because of its constant warmth. Sensitive man that he is, Wasif has a hard time living anywhere with extreme weather.

“You have to imagine seasons here,” he says. As we speak, Wasif is walking but spontaneously decides to sit down in the empty house with a stray cat. The cat is meowing like it’s about to eat his face.

Wasif fulfilled his teenage promise of dedicating himself to songwriting, first in a Palm Desert rock group called Zao, then in psychedelic rock outfit Alaska!, and then in noisy minimalist duo Lowercase. In 2001 Wasif collaborated with Lou Barlow, joining a revamped version of Folk Implosion. All these groups have since disbanded. In 2006 Wasif toured with New York punk trio the Yeah Yeah Yeahs as a second guitarist. He’s been referred to as “the fourth Yeah”.

None of these groups, however, reflect Wasif’s engaging and odd persona. His albums do. In conversation, Wasif speaks about abstract ideas — truth, life and death, the difficulties of understanding himself — with incredible ease. He hardly knows how to talk superficially, and indeed, most of his songs have to do with the difficulties of verbally communicating with others.

“In the world I feel like an alien, in that I have a hard time identifying with a lot of things,” he says dryly. “Music happens to be this one realm where I feel natural.” Playing rock songs, particularly, is the most convenient way he knows to communicate. “There is a pure essence to it… a sort of raw emotion behind it.”

“I don’t feel limited by it,” Wasif continues. “I’ve always been a minimalist. Everything I’ve done musically has been aligned with my beliefs of tapping into a pure emotion and pure essence that can be achieved through these basic ideas. Like conscious asceticism. I can’t envision things in a diluted way. I want them to affect me.”

Wasif’s sincerity verges on the unnerving. Few friends speak to each other with such directness, and when they do, there’s often alcohol involved. Wasif doesn’t drink. He works a lot, rarely goes out, and he hates the bar scene. In the mornings he plays his old songs, over and over, meditating on them until the repetition creates an out-of-body sensation.

Wasif claims to be able to see himself when he goes into this altered state. His current project, aside from playing shows and trying to get a book of poetry published (titled Letters of a Suicide Profiteer), is to create music while he’s in a trance. Listening to Strange Hexes, you’d think he’d already achieved that goal.

And what about fame, the struggle for validation, money, girls and drugs? “Those are illusions of youth,” he says. “I struggle every day in every waking hour to keep all that poisonous stuff outside of me. I want to maintain the purity of what I’m doing.”

As a result, Wasif has a tough road ahead. He decided to release the new album on his own, without the benefits or constraints that naturally come with a recording contract. There are fewer chances to be heard, but then, there is less compromise as well. “I feel mutilated by the business aspect of making music,” he says. He doesn’t care about potential fame. Perhaps the only thing that matters to Wasif is gaining a deeper level of self-awareness.

“I remember at an early age my father telling me my name meant ‘pillar of faith, ‘and that was such a big fucking thing to me,” he says. “At that moment I felt like I had some kind of weight on me that I needed to understand.”

“I try not to think about it,” Wasif adds. But you know he does.