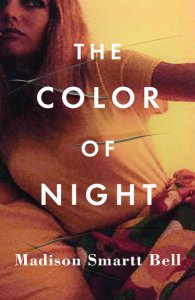

Madison Smartt Bell: The Color of Night (Vintage, 4/15/11)

Madison Smartt Bell: The Color of Night (Vintage, 4/15/11)

The term “revelry” has fallen out into disuse. When you hear it, you think of the Marquis de Sade or Dorian Gray, of a debauched immersion of oneself in the darker yet still pleasurable parts of life, but rarely of something immediate to your own life.

In Madison Smartt Bell’s new novel, The Color of Night, we are made to feel just how current the word still is. When we consider the American public’s obsession with fear, violence, anarchy, and the excessive attention that the news media gives to all of these topics, it’s unsurprising that Bell’s story of revelry rings as true and cuts as deep as it does.

The Color of Night tells the story of Mae, a blackjack dealer in Nevada who develops a strong and immediate obsession with the events of 9/11. She tapes the images of the chaos and blood from news programs (already repeated ad nauseum by the media itself) and, between working at a dead-end job and wandering the desert at night, revels in the endless replaying of so much suffering — for, as Mae tells us, it’s only natural to try and pass your own suffering onto someone else.

She is especially interested in the sight of Laurel, a woman from her past, in one of the clips. From there, Mae leads the reader on a tour of her past, from her suburban childhood as a sexual plaything for her brother, her escape and life as a prostitute in San Francisco, and finally to her time as a follower of D—–, a cult leader in the Nevada desert. It becomes clear over the course of the novel that D—– is actually Charles Manson, but Mae is a true believer, seeing him as the mouthpiece for the Greek god Dionysus.

Bell presents a continuity of orgiastic suffering, of desire mixed with pain, between these three stories — the ancient myth of the Bacchae and Orpheus, the Manson murders of 1969, and finally 9/11. He shows us Mae, who tells her story colored by her belief, and asks the reader to judge just what she is, whether she is the purest incarnation of human nature, a dangerous lunatic, a relic of an ancient ethos, or a mixture of all three.

Mae is a difficult narrator to listen to. Her detachment and regard for other humans as “mere mortals” is an interesting angle from which to tell a story, but as she informs the reader that when her brother repeatedly raped her, it was only to harden her in preparation for life’s troubles, or that D—– would pair off sexual partners from his cult on a whim, or especially when the murders are painted as a half-remembered drugged-out dream, she becomes almost repulsive.

Her story is nearly impossible to sympathize with on an objective level, but Bell’s prose style, with its short, spare sentences, omissions, allusions, and euphemisms, keeps the reader intrigued and voyeuristically fascinated. One early review relates the novel to Cormac McCarthy, an apt comparison considering the mixture of collusion and disgust the reader feels for the narrator. Aside from some overlong descriptions of drug trips and a few go-nowhere subplots, Bell crafts a tight, engaging story.

The question I repeatedly returned to as I read was: why this book now? To most people, none of these events are terribly immediate, but I wondered if Bell meant the reader to connect them to the state of the world now. The news cycle grinds on, just as it always has, but in the last decade (now more than ever) “if it bleeds it leads” hasn’t been sufficient. We need the repetition of phrases and imagery, the indoctrination of fear — but why? Bell suggests that it’s something inherent in our nature, stretching as far back as ancient Greece and before, a need for this sort of revelry in a climate of fear. Mae is an acknowledgment of this need, but rarely a condemnation of it; that’s probably why The Color of Night is such an uncomfortable read. The question becomes not “Why?” but “Are we any better, deep down?”