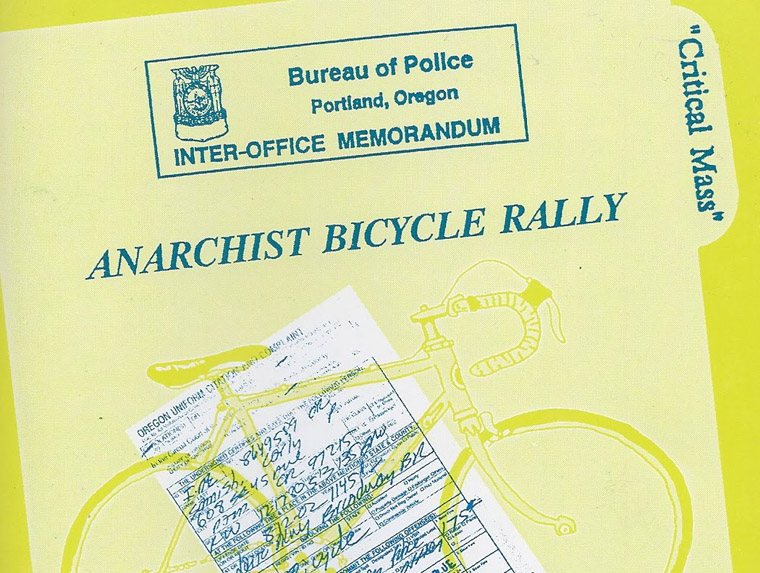

Joe Biel: Anarchist Bicycle Rally: Confidential Mad Libs (Cantankerous Titles, 2011)

Joe Biel: Anarchist Bicycle Rally: Confidential Mad Libs (Cantankerous Titles, 2011)

Many bicycle enthusiasts (and city dwellers) will likely be familiar with Critical Mass. Groups of cyclists ride through urban areas in order to slow traffic and promote cycling over use of automobiles, often using disruption to increase awareness of their cause. Though often a minor inconvenience to some motorists (thus reinforcing the cyclists’ pro-bike message), Critical Mass can be, to hear Anarchist Bike Rally: Confidential Mad Libs tell it, nothing less than a scourge for cops.

Detailing the history of Portland’s Critical Mass movement through 12 years of internal police documents, Anarchist Bike Rally shows the police department’s annoyance, anger, and finally acceptance and cooperation with Critical Mass.

Beginning with documents dating from 1993, Anarchist Bike Rally follows the Portland police as they sit in on Critical Mass meetings, try to predict routes, issue citations, arrest the more disorderly members of the movement, and spend thousands of dollars of police resources to contain groups that, in early years, rarely exceeded 30 participants. Detailed reports follow a narrative that should be familiar to anyone who has taken part in a political action; police confusion gives way to monitoring, attempts to minimize the impact on other citizens, and later communication and cooperation with the activists.

Critical Mass presents a challenge for these cops, however, in that it purposely lacks a clear leader, making the rides that much harder to manage. Trial and error characterizes the police response until the early 2000s, when permitted rides became more common. To make matters worse, early reports show that police seemed to barely recognize the rides as a political statement, instead treating them as unusually organized acts of hooliganism. The riders easily use police confusion to their benefit, avoiding their chaperones and increasing visibility of the rides.

Aside from the odd drunk and disorderly rider and report of aggressive police retaliation, Anarchist Bike Rally lacks in titillation or brutality outrage. Instead, the record of continuous monitoring and accompanying payout for each extra hour of police work makes the police’s dogged pursuit of the riders seem ridiculous compared to the actual size, frequency, and length of the rides.

Some reports show police officers who seemed generally worried for the riders’ safety, as the rides often put them directly in the path of motor vehicles, but most were more concerned with issuing citation after citation for such crimes as rolling through a stoplight — an act, as one rider says, that rarely warrants an official ticket outside of a Critical Mass ride. At its most damaging, Anarchist Bike Rally paints a picture of overly aggressive cops who dislike having their authority flouted by Portland youth.

The Mad Libs conceit (used only in a few documents, thank goodness) wears thin quickly, but it also gives the reports an illicit feel, like censored missives. The real strength of Anarchist Bike Rally is in its repetition of labyrinthine police bureaucracy and the fruitless efforts put into covering the rides, month after month and year after year.

Anarchist Bike Rally makes for interesting reading, especially for those intrigued by the police’s side of this sort of activism. Detailed records of response could even be helpful for those looking to conduct their own similar events. However, Anarchist Bike Rally seems unlikely to appeal to readers outside the politically minded set; perhaps the proposed documentary, Aftermass, which follows up on these reports, will have better success.

The cooperative relationship between the PD and the Critical Mass riders by the end of the zine seems like a sign of better things to come, but for a movement that thrives on disruption and media coverage to make its point, could Critical Mass be losing steam? Anarchist Bike Rally doesn’t analyze or predict, instead focusing on the movement’s evolution from edgy upstart to city-sanctioned parade.