Dirty Three: Toward the Low Sun (Drag City, 2/28/12)

Dirty Three: Toward the Low Sun (Drag City, 2/28/12)

Dirty Three: “Rising Below”

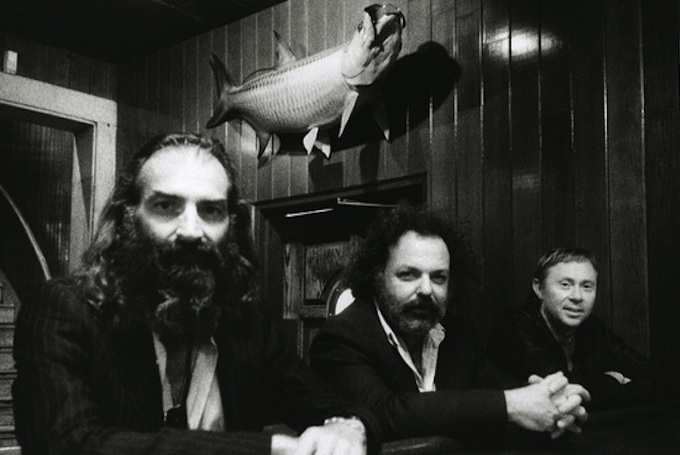

[audio:https://alarm-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/1-04_Rising_below.mp3|titles=Dirty Three: “Rising Below”]It’s been seven years since Aussie post-rockers Dirty Three have released an album. That’s not to say the band members have been lying low: residing in Melbourne, guitarist Mick Turner has kept himself busy with the Tren Brothers and his solo career, as well as his visual art; currently Brooklyn-based drummer Jim White has been touring the world with the likes of Cat Power and Bonnie “Prince” Billy; violinist and recent Parisian Warren Ellis, when not on the road with The Bad Seeds or Grinderman, can be found working with Nick Cave on film scores (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, The Road).

The past seven years have been one of the most creative periods in the band’s history — and it shows on the the trio’s new album, its Drag City debut, Toward the Low Sun. Each member seems to have benefited from the hiatus, as they return with a sound that’s more definitive than ever.

Straying from Dirty Three’s dreamier landscapes, Toward the Low Sun is at times both beautiful and unnerving. There is a renewed intensity to this album, and the band seems to have rediscovered its raw energy, returning to a more jazz-influenced, improvisational approach. Songs like the six-minute post-rock gem “Rising Below” — quietly and slowly building into an anxiety-fueled cacophony — prove that, indeed, Dirty Three is back.

Here Ellis explains the layoff and the new material.

It’s been roughly seven years since your last studio release. What contributed to such a long hiatus? Did you meet as Dirty Three during this time to write or practice?

Many things were at play. I had a lot of work come up with The Bad Seeds and Grinderman and some soundtrack work. Jim was out touring with Cat Power and Bill Callahan and recording with various folk. Mick was doing solo work and painting.

Living on three different continents has its drawbacks. We had been playing sporadically as Dirty Three and had attempted to record a follow-up to Cinder with pretty underwhelming results. There was probably a moment when we wondered if maybe we had nothing else to say, and I guess that’s always been the moment we thought we would hang it up. But playing live was always enjoyable and felt vital and that, in fact, was where we looked for inspiration to record this album. It gave us a way back in, if you like. Practicing has never been a forte of ours; I think we did that three times in the beginning and that was it. Now we do a few days before a tour to kick out the jams and then hit the ground running.

Writing for us has always been a group effort — and we are not the most prolific writers as a group. I think that also having worked in a bunch of groups with vocals, it became apparent that the music Dirty Three made seemed harder to create. The music occupies a very different space. It’s never been about making an atmosphere or soundtrack music for us. We always had to feel there was a narrative to our music — like in a song — but without lyrics, the narrative became harder to locate, and we probably became more discerning. Also, repeating ourselves was never really something we wanted to do. At least, in our minds, it had to feel like each recording moved in a different direction to the last.

What finally brought you back to the studio?

We were really enjoying playing live and wanted to capture this in the studio. I really wanted to wind Jim up and let him go. For my money, Mick’s at his greatest when has little structure and starts to play melodically. I’ve always loved firing off him, and it allows Jim to anchor the whole thing in a loose kind of way. I think we were all missing the freedom we had always thrived in in the Dirty Three, and none of us wanted it to end. But we played some dates in Japan, and I think we saw a way forward there. Once we had verbalized what the approach was, the rest followed. I think it’s the first time we’ve spoken about recording in such a way — like a plan, almost.

How does this album differ from your previous work?

To my ear, I think the album captures something of the spirit of the way we play live, and maybe this was only achieved on our self-titled album. It feels like we have taken the basic premise of the group and stood firmly on it. It’s only a record we could have made 20 years into our career. If anything, I think we’ve tried to take it back to the original spirit of the group, but with the experience we have gathered over the years.

Can you describe your songwriting/composition process? Is it more improvisational, or do you form some sort of preliminary sketch or outline for your songs?

There’s almost always a basic sketch for the pieces that someone has brought to the session. I don’t think to my mind we have ever made a piece up out of some free-form improvisation. Once the idea has been established, we work with it and try to take it somewhere. We try to keep open to improvisation in notes and dynamics, but we are also from the kind of musical backgrounds where we appreciate a tune and something familiar each time we perform a given piece. It’s always been a rather fragile and vulnerable process.

How do you manage your time as a band, considering your geographical distances from each other?

We try to make it work when we can. I think we all realized early on that touring and playing in Dirty Thee full-time was not particularly healthy. It always felt good to do it in concentrated bursts; the intensity of the shows became rather overwhelming in the late ’90s. To my mind, playing in different groups is the best thing that could have happened to us. I’m certain that our longevity is a direct result of this. We try to plan around a show that’s been offered, and know the time is precious, so we have to try and work efficiently.

You’ve collaborated with Sally Timms, Chan Marshall, and Nick Cave as guest vocalists. What do lyrics/vocals bring to a song when your music is already so lyrical? What do you look for in a vocalist when you do bring one in?

Having a full-time vocalist was never a concern to us. We like to use the voice from time to time as another instrument mainly and to see where it might take an idea that felt a voice might be complementary. I think we all were always attracted to the freedom that not having a vocalist gave us as musicians. Certainly, we developed a certain style of playing and had a certain attitude as a result of having no lead vocalist. I really like the fact that not having a vocalist meant we were never misunderstood or misrepresented. We liked the fact that the audience could engage in a personal manner with the music. I think it’s the timbre of the voice that we were looking for when people sang with us; it was never really a lyrical thing.