Sarah Becan: Shuteye (Shortpants Press, 9/26/11)

Sarah Becan: Shuteye (Shortpants Press, 9/26/11)

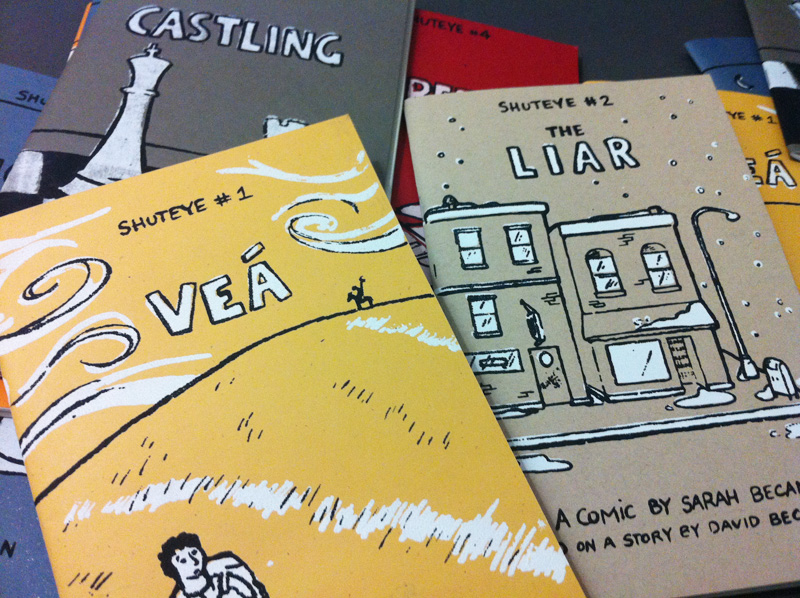

Sarah Becan’s comic book series Shuteye is, appropriately enough, about dreams. In the dream world of the comic book, logic becomes symbolic, coincidences become fateful, and characters learn about themselves in surprising ways. Readers are teased as well; strange things happen in comic books all the time, so how are we to know that this isn’t real? For Becan, the dream state becomes a narrative and stylistic testing ground.

Becan published the first issue of Shuteye in 2005, when her brother had been trying to get some of his stories published. Instead, Becan transformed them into comic narratives, and the first two issues of Shuteye were born. Several more issues followed, each with a silk-screened cover and zine-style binding. The final issue was completed in 2011.

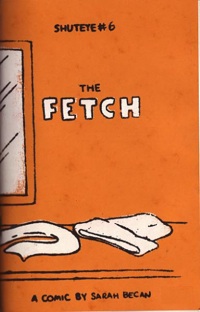

In Shuteye’s sixth and final issue, The Fetch, overworked waiter and boyfriend Jan finds an answer to all of his problems in a mysterious doppelganger. After complaining of a bizarre dream in which his phone call to his mother was answered by Jan himself, Jan’s dream plays out exactly in a Christmas-themed miracle that allows him to be with his mother and girlfriend for the holiday. Soon, the two Jans have a system worked out to their mutual benefit (with doppelganger Jan doing most of the chores), and everything seems fine – until Jan’s girlfriend learns the truth. A surprisingly poignant ending rounds out an entirely unexpected and interesting narrative.

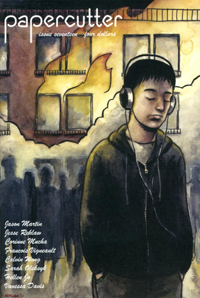

Jason Martin: Papercutter #17 (

Jason Martin: Papercutter #17 (