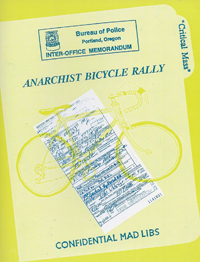

Joe Biel: Anarchist Bicycle Rally: Confidential Mad Libs (Cantankerous Titles, 2011)

Joe Biel: Anarchist Bicycle Rally: Confidential Mad Libs (Cantankerous Titles, 2011)

Many bicycle enthusiasts (and city dwellers) will likely be familiar with Critical Mass. Groups of cyclists ride through urban areas in order to slow traffic and promote cycling over use of automobiles, often using disruption to increase awareness of their cause. Though often a minor inconvenience to some motorists (thus reinforcing the cyclists’ pro-bike message), Critical Mass can be, to hear Anarchist Bike Rally: Confidential Mad Libs tell it, nothing less than a scourge for cops.

Detailing the history of Portland’s Critical Mass movement through 12 years of internal police documents, Anarchist Bike Rally shows the police department’s annoyance, anger, and finally acceptance and cooperation with Critical Mass.

Beginning with documents dating from 1993, Anarchist Bike Rally follows the Portland police as they sit in on Critical Mass meetings, try to predict routes, issue citations, arrest the more disorderly members of the movement, and spend thousands of dollars of police resources to contain groups that, in early years, rarely exceeded 30 participants. Detailed reports follow a narrative that should be familiar to anyone who has taken part in a political action; police confusion gives way to monitoring, attempts to minimize the impact on other citizens, and later communication and cooperation with the activists.

Critical Mass presents a challenge for these cops, however, in that it purposely lacks a clear leader, making the rides that much harder to manage. Trial and error characterizes the police response until the early 2000s, when permitted rides became more common. To make matters worse, early reports show that police seemed to barely recognize the rides as a political statement, instead treating them as unusually organized acts of hooliganism. The riders easily use police confusion to their benefit, avoiding their chaperones and increasing visibility of the rides.

Paul Tobin & Colleen Coover: Gingerbread Girl (

Paul Tobin & Colleen Coover: Gingerbread Girl (