Quannum Projects

Location: San Francisco, CA

Year founded: 1992

Website: quannum.com

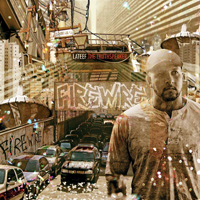

Lateef the Truthspeaker: FireWire (Quannum, 11/8/11)

Lateef the Truthspeaker: “Testimony”

In 1992, a collective of up-and-coming hip-hop artists at UC Davis — future big names DJ Shadow, Gift of Gab and Chief Xcel of Blackalicious, Lateef the Truthspeaker, and Lyrics Born — started up an underground record label called Solesides Records. Seven years later, the label transformed into Quannum Projects, and with the change came a host of esteemed releases that made it an independent hip-hop powerhouse alongside labels such as Definitive Jux, Rhymesayers, Stones Throw, and Anticon.

In addition to its commitment to quality hip hop, Quannum upholds values of ethnic diversity, artistic freedom, and do-it-yourself perseverance, sticking to its roots as a fully independent label throughout hip-hop’s pivotal evolution from burgeoning statement to mainstream farce. In advance of the label’s 20th anniversary, ALARM caught up with Lateef to chat about underground hip hop, his debut solo LP, and “selling out.”

What is your definition of hip hop? Do you think that the rise of mainstream rap diluted the art and culture of hip hop from decades ago?

To me, hip hop is a lens through which you see the world. I think that because the history of hip hop is not really something that is taught or passed on, different generations have different colored lenses. I don’t know if hip hop has been diluted as much as it has simply changed.

Unfortunately, a lot of that change has been dictated to the culture from those outside the culture. When pop culture values become the dominant voice of a counter-culture, the counter-culture becomes a pop culture. That’s kinda what’s happened to hip hop. As the genre became popular, the things that sold were the things that reflected popular culture values more than the values of hip hop. The stuff that sold more was viewed as more successful and (in the eyes of pop-culture values) “bigger.” The values of hip-hop culture were quickly trashed as being invalid.

One example is the notion of “selling out.” At one time, the concept was taboo to the point of rhetoric in hip hop. These days, it’s a key point in most marketing plans. People actually consider themselves lucky if they can sell out. It’s kind of the point for a lot of artists now, the reason they are even in hip hop to begin with.

In a lot of ways, hip hop has been commodified in a way that reduces it to a sales pitch. I mean, a lot of bubble-gum-pop singing acts are tagged as “hip hop” because they wear cargo pants. Crazy but true. It’s just another way that the culture is exploited by those that have no respect or real appreciation for the music or culture. They don’t really care, and nobody’s going after them, so why would they stop?

Still, I think there are a considerable number of artists – old and new – that are still making great music, even in a challenging and rapidly changing musical environment. In some ways, those that are making music in what is increasingly becoming a market wasteland are doing it for purer, more passionate reasons than ever.

That was probably a much longer answer than you were looking for…