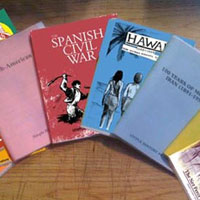

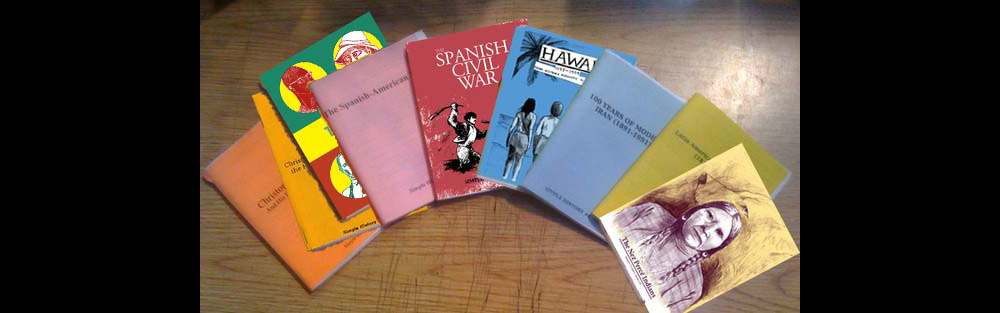

J Gerlach: Simple History Series (Microcosm Publishing)

J Gerlach: Simple History Series (Microcosm Publishing)

The history textbook might seem like an odd choice to adapt to a zine format. On a shelf full of comics, perzines, and essays, you wouldn’t really expect to find a history of modern Iran or the Nez Perce Indians. J Gerlach’s Simple History series (Microcosm), however, aims to change that. Each edition chronicles a decisive moment or movement in world history, condensing a story to the 50-page chapbook format. These books provide an insightful and informative antidote to the bulky historical tome usually found at schools or libraries. Additionally, the presentation breaks significantly with the mainstream idea of “history;” a sort of micro-People’s History of the United States, Gerlach looks at these events with a leftist, anti-imperialist, and sharply critical approach that’s in contrast to many established historical interpretations.

Adam Gnade

Adam Gnade

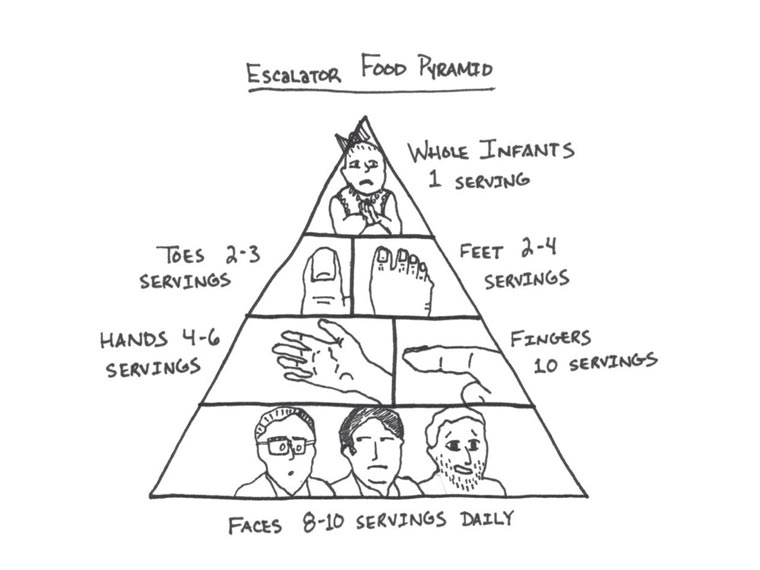

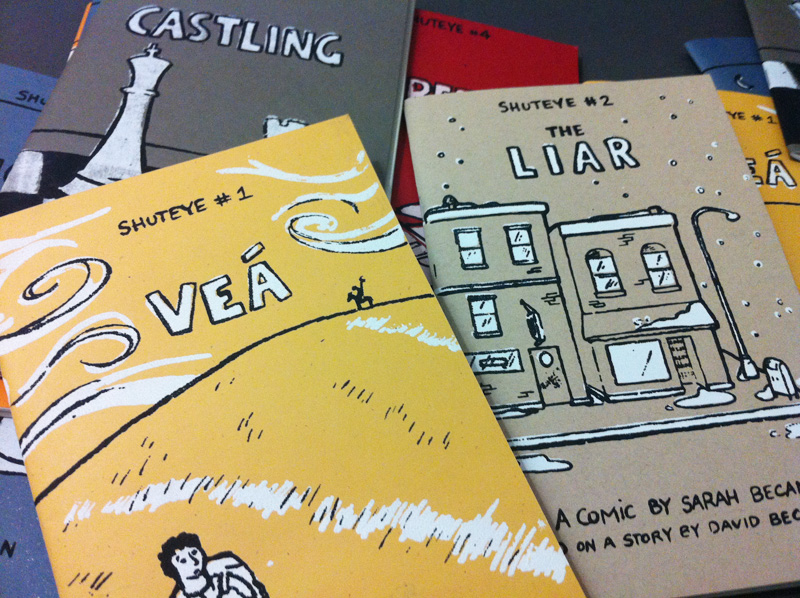

Sarah Becan

Sarah Becan

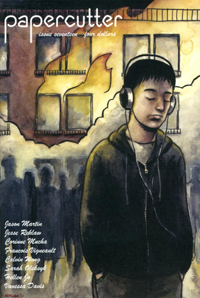

Jason Martin: Papercutter #17 (

Jason Martin: Papercutter #17 (