Moses Avalon is one of the nation’s leading music-business consultants and artists’-rights advocates and is the author of a top-selling music business reference, Confessions of a Record Producer. More of his articles can be found at www.mosesavalon.com.

In part I of our three-part series, “Why You Should Think Twice Before Joining ASCAP or BMI, or SESAC,” we covered the basics of why you might be better off waiting to join one of the PROs. In part II, we are going to examine the widely held belief that these performing-rights organizations are “nonprofit” entities, and how this fallacy affects the way that they both operate. And while we’re un-spinning that, we’ll learn a thing or two about actual nonprofits that might surprise you.

On any music-business panel where the PROs have a presence, this question always comes up: “Why should I join ASCAP/BMI instead of SESAC?” Reps from both ASCAP and BMI will robotically respond, “Because unlike SESAC, we’re a nonprofit organization.”

Is that true? If so, does being a nonprofit mean that you, as member, will get more cash? What if it was all a lie? All of it. Would that lie make you leery of other claims that ASCAP and BMI make about your benefits?

It’s not too hard to figure out why someone would claim to be a nonprofit; when people think of nonprofits, the word “charity” is usually not far behind. It also fosters the image of employees flying coach, eating bag lunches, and working tirelessly at a thankless job.

But, in truth, ASCAP and BMI are among the richest entities in the music business.

What exactly is a “nonprofit”?

From the IRS’ point of view, “nonprofit status” means one main thing: after you pay all of your expenses, any remaining money must be paid out to your members or your cause, thus leaving no “profit” left to distribute to stock holders — or anyone, really. This is true, even if you have 99 cents worth of expenses on every dollar that you make and give only a penny to your cause. The caveat being that it must be 99 cents worth of “legitimate and necessary expenses.”

ASCAP claims to have the highest cost/payout ratio (called a “cost/benefit ratio”) of any PRO in the world — 13.5 percent — meaning that 86.5 cents of every dollar that it collects goes to its members. BMI claims on its website that its overhead is only 15 percent, meaning that 85 percent goes towards its members. These are acceptable percentages, comparable to any legitimate, tax-exempt nonprofit charity. Save the Children, which pipelines donations to underdeveloped nations, has a similar cost/payout ratio, so it’s no surprise that the PROs would emulate that type of organization.

ASCAP and BMI both claim that after covering their necessary expenses, they pay out all remaining money to their members, leaving no “profit” at the end of each year. But what do the PROs consider “necessary” to spend your money on? A few facts:

– The CEOs of both ASCAP and BMI receive annual compensation well into the low seven-figures. Executives are paid quite well too.

– Both have offices in prime real estate in Manhattan and Los Angeles, where cumulative rent approaches millions of dollars per year.

– Both throw lavish and expensive parties designed to rally new members and give away huge cash awards.

– Everything listed above costs each PRO about $100,000,000 per year in “expenses.”

Big parties? Huge salaries? Fancy offices? A hundred million bucks a year in overhead? Does this sound like a charity or any nonprofit that you are familiar with? Are any of these expenses truly “necessary” to collect performance fees that are due them by law?

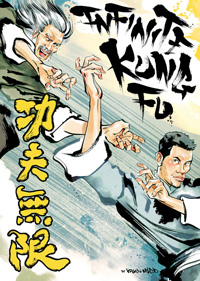

Kagan McLeod: Infinite Kung Fu (Top Shelf, 9/13/11)

Kagan McLeod: Infinite Kung Fu (Top Shelf, 9/13/11)